Science

Power from an “Artificial Sun”: The Global Race for Clean Energy

08 February 2026

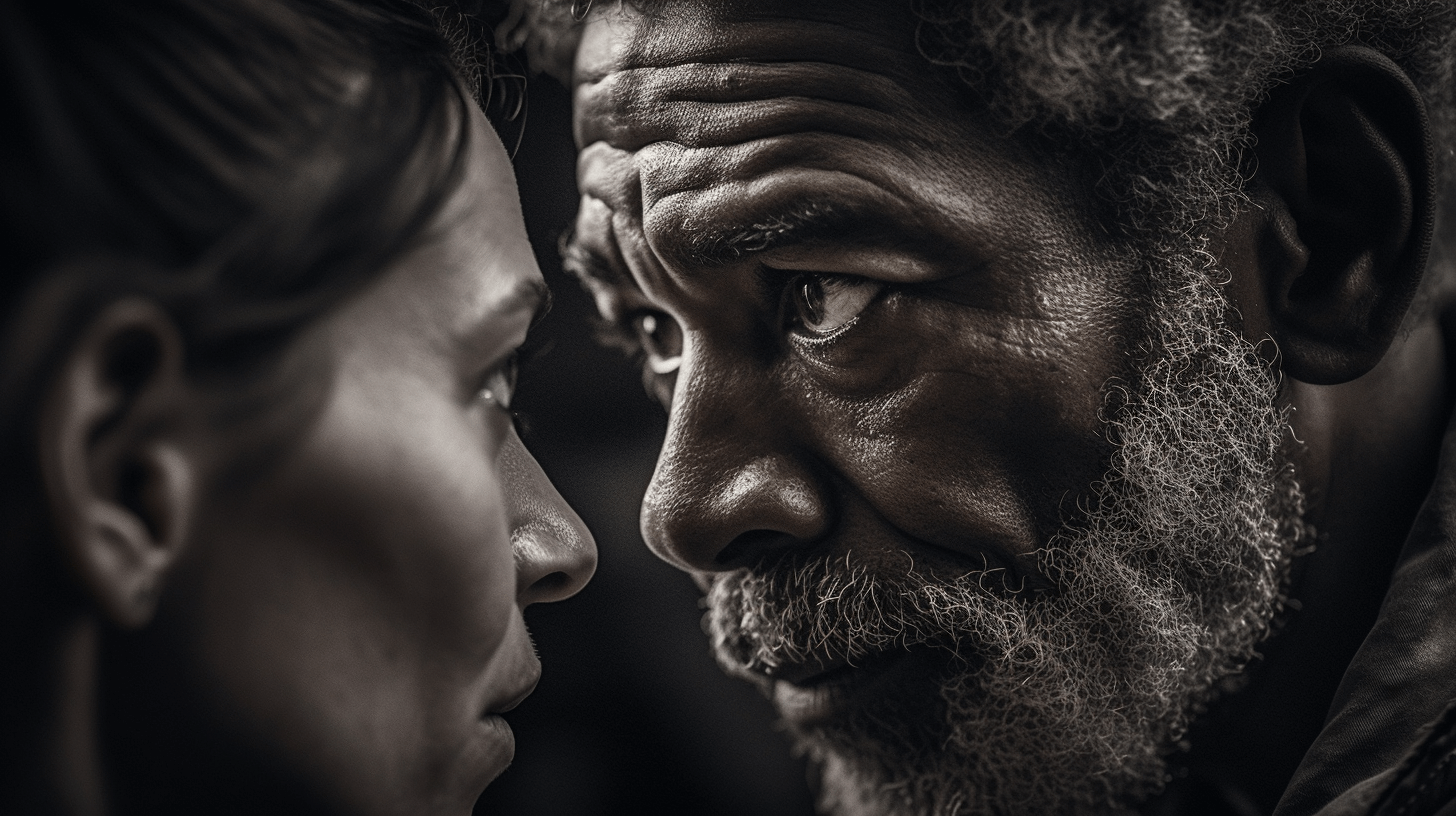

Józef Tischner (1931-2000), a proponent of the philosophy of dialogue and encounter within the realm of Polish humanistic thought, once remarked, “Dialogue signifies that people have emerged from their hideouts, drawn closer to one another, and initiated an exchange of views. The onset of dialogue – the act of emerging from hiding – is already a momentous event. It requires one to venture out, cross a boundary, extend a hand, and find a common ground for discussion.” Where does the contemporary individual find himself in his life’s journey? Do we seek interaction with others because we recognize the necessity of dialogue, or conversely, do we increasingly seek refuge in our private sanctuaries, shielding ourselves from a world that holds the potential for harm? And if we do desire conversation, are we adept at it?

As defined in the dictionary of literary terms, ‘dialogue’ (from the Greek ‘dialogos’ – conversation) denotes the exchange of sentences between at least two individuals on a specific subject. Yet, our daily experiences indicate that while we may exchange sentences, relay various messages, and impart information with numerous individuals, we intuitively sense that this does not equate to engaging in conversation with them. It appears that the occurrence of a dialogue, a genuine conversation, necessitates the prior fulfillment of several conditions which facilitate close contact with another individual. Are we cognizant of these prerequisites in our daily interactions with others before we assign blame and express regret for unsuccessful conversations, overly emotional disputes, or communication that fails to culminate in mutual understanding?

To initiate a dialogue, one must first experience another person by encountering them. Józef Tischner argued that encountering someone is more than just being aware of their presence. Although we interact with many individuals daily, merely passing by or bumping into someone does not constitute a meaningful encounter. A true encounter is transformative for both parties involved. It involves consciously choosing to engage with a specific individual from a crowd and dedicating one’s attention solely to them. This conscious choice to engage in dialogue necessitates respect for the other person’s uniqueness and differences.

French existentialist philosopher Gabriel Marcel contended that to truly know someone, one must first allow that person to exist as they are. Many proponents of the philosophy of dialogue and encounter underscore this precondition as essential for meaningful conversation. The other person is fundamentally different, coming from a unique background, carrying experiences unknown to us, and holding potentially contrasting views, opinions, values, and principles. The act of encountering facilitates a mutual openness, a willingness to understand and know the other. Demonstrating mutual respect involves a readiness and eagerness to understand the other person, to learn about their identity, and to discern what they are willing or unwilling to share. Such an approach is pivotal for fostering dialogue. “Allowing the other to be” implies a receptiveness to their uniqueness and distinctiveness, coupled with an attitude of affirmation and kindness.

Each of us can stand in front of a mirror and perform a brief “examination of conscience”: how often, when encountering another person, do I already have prejudices and suspicions in my mind that only arouse my fears and apprehensions towards the person I meet? How often does the first impression, as the name suggests, only the FIRST impression, already define me in relation to the Other and prompt me to draw a ready conclusion? How often do we judge others by their appearance or by a heard opinion? Am I truly capable of respecting their differences and wanting to understand them, or is it easier to judge from above without the will to understand? Are we able to give each other time for mutual acquaintance and expand the space for dialogue, or is fifteen minutes of conversation enough to discredit, reject, or negate someone?

For dialogue to be possible, ethical awareness is also necessary, which must accompany the interlocutors who enter into the space of the encounter. Tischner wrote: “A man stood before me and asked me a question. I don’t know where he came from, and I don’t know where he is going. Now he expects an answer. By asking, he evidently wants to make me a participant in some of his affairs […]. What can I do? I can answer or not, I can answer senselessly, evasively, falsely. It is certain that I do not have to answer – I can turn into a stone that does not hear.”

Every interaction initiates an ethical dimension. This signifies that the mere act of engaging in conversation immerses us in a realm of values. If I am invested in the interaction and wish to foster a dialogue, I must actively participate. Often, a conversation begins with a question, essentially a form of request. In asking, we seek an answer. We desire to learn something; we are intrigued by the other individual. Posing a question is an attempt to bridge the gap. The questioner wishes to welcome me into their world. Will I reciprocate? I could, after all, dismiss the question directed at me. I might deem it irrelevant, foolish, or naive (in my assessment), completely overlooking that for someone, due to reasons known to them, the question held significance. How frequently do we dismiss others’ questions, merely because we assess them from our own vantage point? At times, questions appear overly audacious; some seem excessively invasive or even presumptuous, and rather than seeking clarification on the questioner’s intent, we prefer to abstain from responding altogether. We may not even wish to comprehend, as it would demand a greater effort in terms of time, probing, and demonstrating heightened interest.

Tischner advises against evasion and self-isolation, as doing so eliminates the very possibility of dialogue: “I respond because the question is both a plea and a call to action, and the plea and call to action establish ethical accountability. I respond to avoid harm. If I remained silent, I could inflict damage on the questioner. My silence would represent an act of disdain. A response is necessary.”

These words unveil the ethical aspects of an encounter and the endeavor to establish a dialogue. By responding to a question, I am addressing someone’s plea. I provide what I was solicited for, thereby not remaining indifferent or underestimating the other person’s needs. In doing so, albeit to a modest degree, I assume responsibility for the other. The term “responsibility” inherently includes the word “response,” which, from an ethical interpretation standpoint, implies that responding equates to assuming responsibility: for the other, for oneself, and for the shared conversational space.

Our interactions create a realm of encounters and separations. How we engage in dialogue either draws us nearer to others or pushes us further away. Our mindset and responses dictate the outcome of our encounters with the ‘Other’. Tischner posited that the foundation of our interactions is a broad array of ideas and values. In a dialogue, we selectively embrace certain values while dismissing others. If my reaction is a barrage of expletives, I am embodying aggression and violence. Conversely, demonstrating patience and a willingness to understand aligns me with benevolence. Following the Austrian philosopher and religious scholar, Martin Buber (1878-1965), who stated that “all real living is meeting,” the fate of future encounters rests solely in our hands. It is crucial to acknowledge that without a shared basis for understanding and a commitment to constructive discourse, personal growth is unattainable. Humanity’s advancement hinges on our capacity for dialogue because it empowers us to realize our objectives and envision our future.

Polish journalist, essayist, and poet, Ryszard Kapuściński (1932-2007), observed that there are “few who ask questions and many who know everything. When someone does ask a question, it is worth giving them attention, as it indicates a person who is searching, reflecting, and trying to understand, which is exceedingly rare these days.”

This insight urges us to value every question we are asked. It represents a person’s ongoing desire to comprehend, explore, and aspire, which is why they often seek our help and support. Such a request for a response holds ethical significance because it compels us to participate in the questioner’s life and to collaboratively create. Without this exchange, without co-creation, we are left with only the refuge referred to earlier. A haven that signifies isolation, disconnection from society, and immersion in one’s ego. American author and journalist, Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), while portraying the challenges faced by a lone man against the sea, aptly noted: “The old man realized how pleasant it was to have someone to converse with, instead of just talking to oneself and the sea.”