Truth & Goodness

Why the Space Age Never Truly Arrived: A Failed Cosmic Promise

09 March 2026

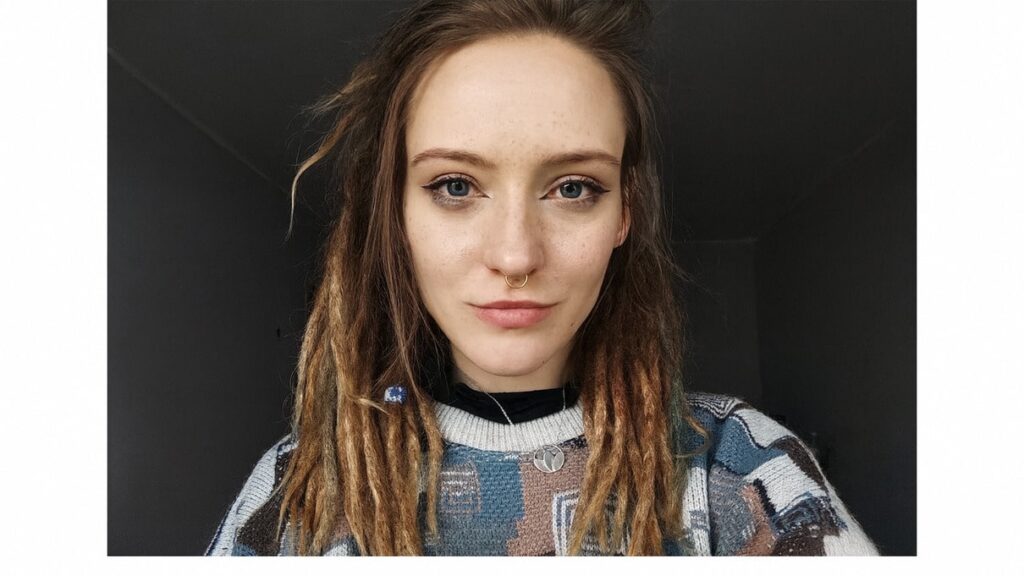

Selling intimate recordings and photos, or so-called cam sex – in the age of the internet and social media, prostitution adopts increasingly new, more visible forms. Trading one's body is often associated with the illusion of massive earnings, liberation, and independence. “This is a distorted image of female empowerment,” says Weronika Brykalska, an activist from the Bez Association, which fights against the erotic exploitation and violence faced by women.

Anna Bobrowiecka: Why has prostitution—something that always symbolized downfall, was stigmatized, provoked contempt, and was synonymous with the gutter and social margin—become normalized, equated with women’s emancipation, and idealized in recent years?

Weronika Brykalska: I believe this stems from a distorted image of female empowerment. Prostitution was historically judged harshly, not just as a phenomenon, but specifically the women involved in it. People considered them damaged, immoral, and lacking self-respect. Today, some media and communities promote the vision of prostitution as work that gives women not only independence but also certain power over their own lives and over men. They push this as the opposite of the original perspective. However, this idea is quite warped, as I mentioned, because it unfortunately ignores the consequences that come with prostitution.

What is the most common, true image of a prostitute today? Is she still a provocatively dressed woman soliciting clients near the woods?

Street prostitution certainly still exists, but it is definitely less frequent than it used to be. Simply put, other options emerged. First, we must acknowledge that women who become involved in prostitution usually find themselves in a critical life situation—for instance, facing extreme poverty or experiencing violence. In these circumstances, the first thing that may come to mind is selling sex on webcams, sending photos, or creating pornographic material.

This is certainly a safer form of prostitution than the once most common street work. There is no direct sexual contact with clients, so there is no risk of venereal diseases; women also do not need to fear rape, assault, or murder. Nevertheless, this approach rests on the assumption that women will never meet clients in person, which is often very misleading.

Girls involved in this “modern” prostitution typically promise themselves, for example, that they will only communicate with the client online, that they will only send photos, and that they will not have sexual intercourse with clients. They tell themselves they will not cross that line. Yet, these boundaries shift very quickly. When a woman needs money and realizes she won’t earn anything unless she strips, meets the client, or satisfies their demands, she will be willing to move those boundaries. She will do what ensures her survival.

To sum up, while this contemporary prostitution is theoretically not as extremely dangerous as direct contact with clients, it still carries various risks. We must also remember that nothing truly disappears from the internet.

What does this mean for them?

Internet prostitution obviously involves sharing one’s image online, usually with complete strangers. Thus, their face often does not disappear from the internet “when it’s all over.” Photos or recordings can be used later to create deepfakes or they may appear on other pornographic platforms. Such women are very often afraid of being recognized; they fear going outside or taking on a regular job. This online activity leaves a permanent mark, which later generates enormous anxiety.

Let’s stay with the “traditional,” street prostitution for a moment. How do the people involved try to break away from it, and how often do they succeed?

I should start with the most important data point we often cite: studies show that around 90 percent of women in prostitution want to leave. However, we do not have data on how many women actually succeed, primarily because we do not know the exact number of women currently involved. Coming back to your question—how do they try to leave and do they succeed? It depends. Primarily on their options and whether they have somewhere to go.

If we talk about victims of human trafficking, confined to brothels and deprived of their passports, they are physically unable to leave the location where they are held. However, prostitution is often also associated with psychological dependence. Some women work independently, without a pimp. Nevertheless, they are unable to quit because the easy influx of quick cash releases dopamine, which can be addictive.

Addiction is an additional, serious problem here—people in prostitution often fall into alcoholism or drug use. These substances allow them to survive the day. They use them to relieve enormous stress and pain. Clients themselves often want the women they buy to do a line of coke or have a drink with them. In such circumstances, breaking away from prostitution and returning to a normal life is even more difficult—quitting prostitution means leaving the “source” of acquiring substances. As I mentioned, leaving also depends on whether the woman has anywhere to turn for help. And here lies another problem.

Not from the state and its institutions. In prostitution in Poland, assistance for people in this situation is provided mainly by third-sector organizations—foundations and associations. Besides the Bez Association, Feminoteka or the Women’s Rights Center also operate in this area. But do we have a system of social assistance in Poland aimed strictly at women in prostitution? Unfortunately, we do not. The solution introduced by Sweden (the so-called Nordic Model) is definitely noteworthy. They have various centers women in prostitution can approach to receive support.

At the Bez Association, we also try to help these individuals to the greatest extent possible. Sometimes, however, women come to us saying they want to quit prostitution, but when we enter the process of support and tell them what we can do, they, for example, withdraw from contact with us. They are not ready for it yet, for various reasons. Prostitution acts a bit like a toxic relationship: it definitely affects a person very badly and causes harm, but it is also addictive and, in a way… safe.

Exactly, because it is familiar. It is something these women are used to. Moreover, they are very often confined to a rather small environment. They do not have friends outside of prostitution because they feel ashamed of what they do. This shame blocks them. They do not know how to return to the job market or how to build normal relationships. That shame can be so significant that they decide to remain in the trade of their bodies.

We have already started discussing the consequences of prostitution for those involved. What are they—physical, health, psychological, material?

Regarding the psychological consequences, over 60 percent of prostitutes experience symptoms of PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder. This scale is comparable to that of war veterans. Most women who contact us ask for help finding therapy. Secondly, they also suffer consequences in interpersonal relationships—problems with trust and an inability to form relationships (especially romantic ones). If a woman only has contact with men who treat her as an object for a period, it is not surprising that she becomes prejudiced against men in general.

We should also mention problems with sexuality. Sex for money is not the same as what people outside of prostitution know. It is sex during which a woman must “separate” from her own body, experience dissociation and derealization to survive it. Therefore, it is not surprising that these individuals’ later return to “normal,” healthy sex involves numerous blocks and difficulties, such as flashbacks.

Regarding the physical consequences, violence, rape, and sometimes even death at the hands of a client are, unfortunately, commonplace. It is worth mentioning the less obvious and drastic ones—these often include problems with the weakening of the uterine muscles, venereal diseases, recurring vaginal infections, and problems with urinary and bowel incontinence. These ailments affect even women in their twenties working in prostitution.

Furthermore, they also face skin problems—especially if they work in a place with poor hygiene. Most of these ailments result simply from the body being excessively overloaded by overly frequent sexual intercourse. The constant stress these individuals experience usually causes sleep problems—most women in prostitution complain of insomnia.

The material consequences largely boil down to one fundamental problem: a lack of any livelihood security. Even if a person in prostitution earns significant money, if anything happens to them—they get sick, break a leg, become unable to work—they are left alone, without means of subsistence or support. However, even if a person in prostitution got insurance and could take sick leave, this does not change the fact that this work is, and always will be, simply dangerous. Illness or painful menstruation become the smallest problem when we consider the risk of rape, assault, or murder.

Precisely. Advocates of legalizing and taxing prostitution argue that all these risks and threats will disappear when the state regulates the conditions of “sex-working” and provides these individuals with insurance, holidays, or sick leave. There is even talk of creating special, clean, and controlled spaces where these individuals could “safely” sell their bodies.

I believe that even if we built brothels in palaces and prostitution was covered by the best insurance, nothing would make it a proper activity. Prostitution is “work” in quotation marks. It involves sexual contact with strangers who treat the person providing these services as an object. Look at it analogously—if a person in a normal, healthy relationship had sex with their partner for several hours every day, they would also face bothersome physical consequences. And here, we also have the aspect of danger, because the clients of prostitutes are not simply lonely, harmless men seeking company. They are, to a large extent, dangerous and aggressive.

The moment a man goes to a woman and pays her for sex, he demonstrates that he does not treat her as a human but as a commodity. Therefore, we believe there is not and never will be any question of genuinely ensuring safety or comfort in this “profession,” and we will not eliminate the tragic consequences of prostitution—regardless of what social measures or conveniences we try to implement there. Prostitution is also an intrinsic evil from a certain moral perspective: we consent to the human body being commodified. People who postulate the legalization or decriminalization of prostitution and its recognition as work agree to let capitalism commodify all spheres of our lives. We permit everything to be for sale.

The argument is often raised that no hired work in late capitalism is voluntary and that we exploit our bodies in some way in every job. However, we cannot talk about sex as work like any other, because we cannot talk about sex as an activity like any other. This is a very delicate, intimate sphere of a human being that requires immense care. Healthy and safe sex only occurs after enthusiastic consent, and sex for money will never be sex with enthusiastic and genuine consent, because that consent would never appear if its monetization was not involved. Therefore, in our assessment, bought sex will always be paid rape.

As we have mentioned, new forms of prostitution have emerged—primarily online. Its scale is growing and becoming more popular; more girls and women are choosing this activity, especially with increasing social permissiveness and growing demand for such services online. Is this a phenomenon that can still be reversed without penalties and restrictions?

In my opinion, we have enough technological capability that if the elites and authorities cared about eliminating online prostitution, it would disappear. All websites offering this type of content and services could be very quickly identified and deactivated using appropriate tools. Unfortunately, this is not profitable for the elites, because the owners of pornographic sites or portals like OnlyFans make huge money from it. The owner of OnlyFans takes only 20 percent of what women earn on the platform, yet the platform’s annual earnings have already reached several hundred million dollars. The creators of this portal advertise it by claiming that women receive the vast majority of the profit for themselves—but they themselves still get the richest. Neither politicians nor the owners of such businesses benefit from decriminalizing or restricting this practice.

Of course, we cannot get rid of such platforms quickly and easily, but it is worth noting certain legal solutions implemented abroad. For example, Sweden recently recognized online prostitution as the same form of prostitution as any other and banned paying for such sexual services. This obviously significantly reduces the problem within Sweden itself. If the authorities of other countries and representatives of the technological industry also wanted to wage a larger-scale war against this phenomenon, much could change.

What we can do is pressure politicians, but above all, we must bring attention to the problem, debunk this false narrative of “legal, safe prostitution,” and help women who want to leave. I believe that as an individual, I cannot make prostitution disappear from this world, but I can certainly talk to the women around me and show them the consequences associated with trading their bodies.

Sometimes girls contact us saying they intended to enter prostitution, that they were very close to setting up a profile on a pornographic site, but they didn’t do it because they came across our content and realized what that would entail. And this is what we can and should focus on right now. We still have a long way to go until prostitution completely disappears—but I believe it is possible, and that goal drives me.

Read the original article in Polish: Handel ciałem jako praca? To niesie skutki, o których się nie mówi