Science

The Sun’s Ring of Fire and a Planetary Parade: A Captivating Celestial Show

13 February 2026

This is a great human strength – we can encode the past, we can imagine the future and talk about it. And this happened precisely because we use language. The productivity of language detaches us from the "here and now," explains Prof. Aneta Wysocka from the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin in an interview for Holistic News.

Maria Mazurek: How did languages originate?

Prof. Aneta Wysocka:* This question intrigued the greatest minds long before linguistics even existed.

What is the answer?

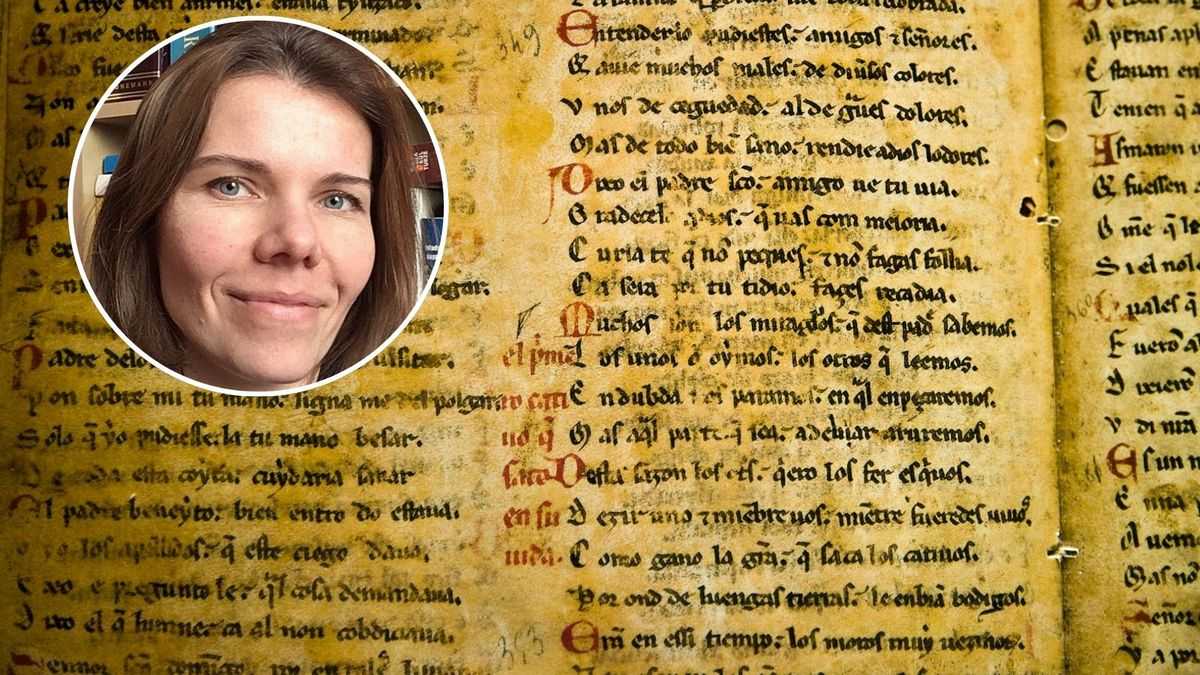

We don’t know it. Speech leaves no fossils. The only evidence of the shape of ancient languages is writing. But a vast amount of time passed between the moment natural languages were born and the moment people began to record them. We are forced to rely on guesses—or perhaps on tracking traces.

What kind of traces?

We have certain anthropological clues: the position of the larynx or the size of the brain estimated based on the shape and size of the skull. Based on this, we can formulate hypotheses that humans became capable of very precise articulation hundreds of thousands of years ago. And that was necessary to use language as we understand it today.

I asked about the origin of languages. What exactly is language?

I will answer from the perspective of a linguist – a productive system of symbolic signs.

Could you tell us how to understand that?

To put it simply: from a limited repertoire of symbols—or, simplified, words that we use to name things and phenomena—we are able to generate an unlimited number of sentences describing various states of affairs. Those that occurred in the past, those that exist now, those that might exist in the future, and those we can only imagine.

Is this possible thanks to grammar?

Yes. Grammar is nothing more than a rule for combining symbols into utterances. It enables this “productivity.” There are many communication systems—both those that evolved naturally and those created by humans—but only natural language meets the condition of productivity. We know that animals have ways of communicating (more or less advanced, more or less understood), but we have no evidence that they meet the condition of productivity.

So we don’t know how the origin of languages occurred. Do we know if they all come from a common “protolanguage,” or did they develop independently of each other?

We have alternative hypotheses. And too little knowledge to grant priority to one of them.

If it’s true that languages were born independently, could they be “hardwired” into our brains?

There is such a hypothesis popularized by cognitive scientist Steven Pinker. Pinker wrote a book titled The Language Instinct, which contains the thesis (well-documented, by the way) that using language is an instinct in humans—an innate and not necessarily conscious mechanism.

So he places it alongside maternal instinct, self-preservation, or reproductive instinct?

Yes. Pinker believes that language is biologically “built-in” to us.

And what do you think?

As a scientist, I try not to favor any hypotheses as long as data is lacking. And in this case, we still know too little.

What do we know then?

We certainly know that young children have a natural inclination and need to acquire the natural language spoken by those around them. They want and are able to learn incredibly quickly which categories are worth dividing the world into to navigate it better. To name what surrounds them. They also have a need to communicate with another human being. We also know that there is a developmental window of a few years during which a small person should “fit in” to acquire language. Later, it becomes much more difficult, though not impossible.

Does language have to be verbal?

Verbum means word. A word is a symbol—a symbol we have in our minds. It is a secondary matter how it manifests itself. It can manifest as speech—a stream of air shaped by our articulatory apparatus—or it can manifest as a sequence of signs on writing material—on a computer screen or a piece of paper written with a pen. But it can also manifest as a symbolic gesture. We deal with symbolic gestures in the case of sign language. There is no doubt that it is a productive language—one can express all our thoughts about what was, is, and will be through it.

What was, is, and will be – is that the key?

Yes. This is a great human strength – we can encode the past, we can imagine the future and talk about it. And this happened precisely because we use language. The productivity of language detaches us from the here and now.

You called it a human strength. Others would call it a curse. After all, mindfulness, meditation, yoga, certain forms of therapy – all of these are meant to help us be “here and now.” To stop, if only for a moment, this chase of thoughts – into the future, the past, through various threads and topics.

Hence the utopian idea of returning to nature. We have a suspicion—or perhaps we would very much like it to be so—that returning to primal forms of existence would ensure our well-being. But would it really be so? I don’t know, but I don’t think I would give up the ability to look into the future and explore the past just to feel good.

Me neither. But I would like to stop the flood of thoughts sometimes.

Like most people.

And are thoughts always language? Are there non-verbal thoughts?

Of course, there are. Cognitive psychology distinguishes between different types of thinking. Engineers, when solving spatial problems, do not have to use language in that process. Not all thinking is linguistic. However, language, words, and linguistic symbols are anchors for thoughts.

I asked this question because it seems to me that my thoughts are always words. But when I asked others about it, the answers were different.

A great asset of our species is neurodiversity. Because we are different, yet function within a community, we can use these specific traits for the benefit of all. There are engineers who think spatially, who can mentally rotate geometric figures, which I can’t even imagine. And there are those who think mainly through language, and thanks to them, we have wonderful literature.

And does the language we think in determine our way of understanding the world?

I wonder if “determines” is the best word. I think I would prefer to say: facilitates.

Why?

Let me explain: language contains certain interpretations of reality made by our ancestors that proved useful. So we, by learning words, also learn models of interpreting the world. The first language—which will always remain the most important one—organizes our cognitive system. Of course, every language is productive, so we can express everything in it. But the language we use (especially the first one) directs our attention to those categorizations that are already ready, served to us on a platter. It suggests an interpretation of the world. We can be satisfied with that, or we can look for alternative visions of reality—and still use the same language. So it is always a matter of cognitive activity. That’s why I wouldn’t speak of determinism here, but rather of what is easier and what is more difficult. And whether a person wants to take the trouble to see the world differently.

There are elementary words found in every language in the world. However, most words are specific—specific to a given language and culture. I recall a beautiful lecture by Prof. Anna Wierzbicka about the word pamiątka (souvenir/keepsake), which the professor considers a word specific to the Polish language. Although we can translate it as “souvenir,” we lose what it carries with it. The word pamiątka shows our culture’s established attitude toward the past, toward time. Even toward other people.

There are also words that are completely untranslatable.

Perhaps I should put it differently: translatable, but having no single-word equivalents in other languages. The German Reisefieber can be translated as “a state of nervousness before a journey,” but we need a whole phrase for that. Finns have one word for the heat given off by stones in a sauna. These are anecdotal examples—interesting, sometimes funny—but they show that our culturally conditioned interpretations of the world differ. So learning a second language is not only about acquiring tools for communication but also new tools for thinking. A new language opens up a new image of the world for us.

* Dr. hab. Aneta Wysocka, Professor at the Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin – linguist, academic teacher, and member of the Program Board and Board of Directors of the “Akcent” Eastern Cultural Foundation. She is the co-founder and scientific editor of the linguistic yearbook “Idiolekty” (Idiolects). Her honors include the Medal of the President of the City of Lublin and the Cross of Merit of the Republic of Poland. She is the author of numerous books and scientific publications on language.

Read the original article in Polish: Wciąż nie wiemy, jak powstają języki. Prof. Wysocka szuka odpowiedzi

Science

13 February 2026

Science

13 February 2026

Science

12 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny