Science

Hidden Depths: Thousands of Unknown Viruses Found in the Dragon Hole

16 February 2026

Discussions on the commons typically evoke a certain discomfort. Initiators tend to resort to pathos, while for the audience the topic borders on an idealism associated with a lack of knowledge about “real life.” In the worst case, the discussion is reduced to the absurdity of sharing a toothbrush. Yet the history of common goods recalls what’s most fundamental: solidarity, community, self-governance, and localism. In a sense, these are the elements lost in the modernization process based on free-market principles, encompassing a range of social, technological, and economic changes that have been ongoing for over two centuries.

Currently, though, there is a renewed interest in the concepts of the commons. This is because as a society we are in crisis, which the philosopher Bruno Latour has aptly diagnosed. Classical economics and its assumptions remain the leading model for economic management. However, they need to be redefined. The need for immediate change is evident on many levels. It must be acknowledged that cooperation manifests at the level of local communities. The turn away from acting at the local level has led to lacks of awareness and responsibility among citizens about common goods, partly fueled by inadequacies in education. Meanwhile, the solution to today’s societal crisis lies precisely in exploring theories of the commons and acting at the level of local communities.

First, let’s clarify a few fundamental matters: what are the commons? They emerge when a group decides to collectively manage a specific resource. Common resources include cultivated land, fishing grounds, urban space, source codes, groundwater, parking space, and bridges. The commons are also considered in a global context, known as global commons, where forms of ownership operate under international law, exempt from individual states’ sovereignty. This includes the air, seas and oceans, outer space, and the Antarctic continent.

The concept of commoning is gaining popularity in Europe. Its principles are based on the idea that communities should strive for commoning resources to protect them from enclosure, depletion, commodification, and exploitation. Advocates of this model, known as commoners, emphasize people’s right to use the commons in fulfilling basic needs, prioritizing it over market exchange and capital accumulation. Commoning extends beyond establishing something as a common resource; it also involves caring for, protecting, and regulating access to a resource through developing internal mechanisms for collective management and the ongoing redefinition of boundaries of common goods.

Read also:

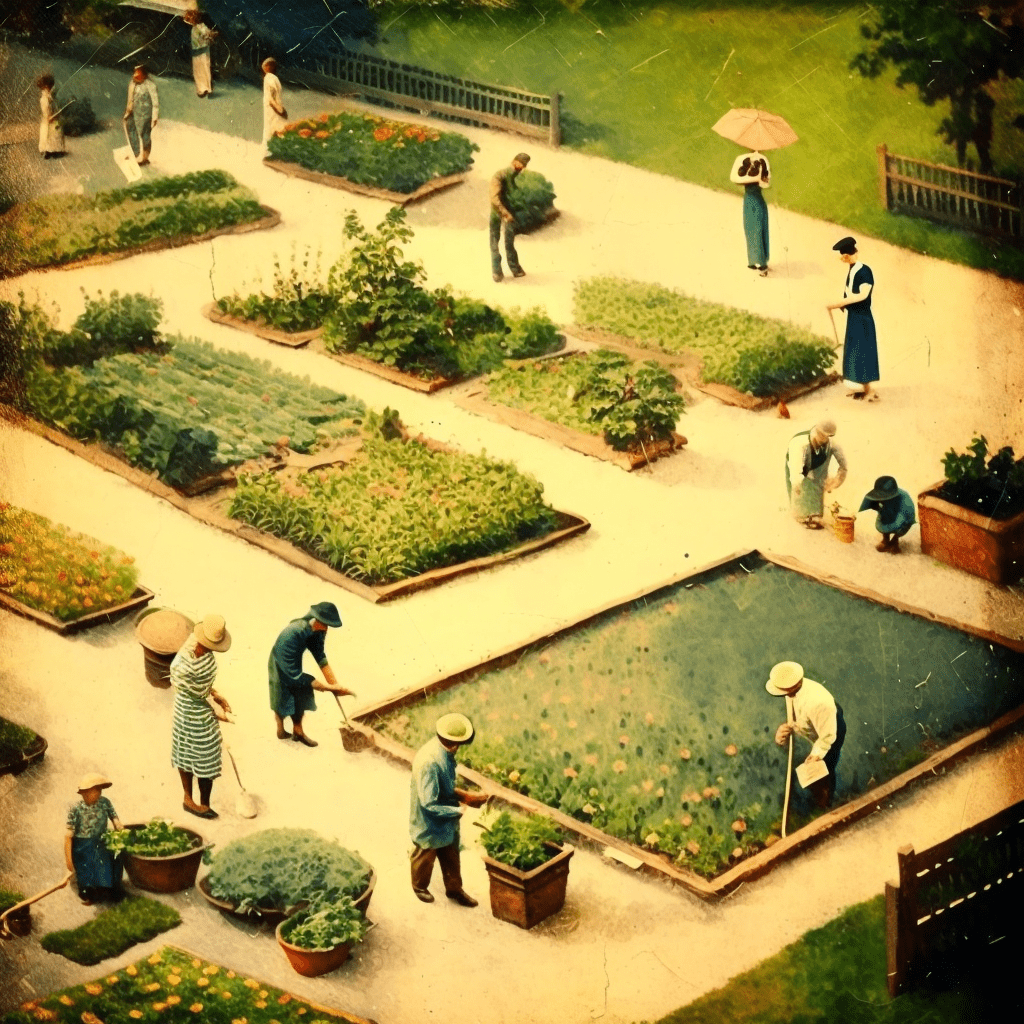

The sources of contemporary interest in theories of the commons can be found in activism’s growing popularity at the urban and rural levels, as well as in rural protest groups. Among the motivations driving the emergence of these organizations, let’s highlight attempts to end the dominant duopoly the state-market represents and critiques of neoliberalism with its aim of privatize various aspects of public life. To exemplify this: care for the commons is manifested in establishing community gardens as much as in indigenous inhabitants’ struggles in the Amazon’s rain forests against illegal logging and settlements in protected reserves.

In fact, the need for immediate change is evident on multiple levels. One of these is education, where fostering the sense of civic solidarity is an extremely deficient or rather dysfunctional process. Many of us aren’t aware of how our taxes are actually being used. The striking lack of awareness about the functioning of society undermines the foundations of urban communities. We need educate young citizens about where our waste is sent and where electricity powering street lamps comes from. This way, we lay the groundwork for future local communities. Actually, emphasizing relational aspects of social life is a practice being employed by contemporary commoners.

As a society, we find ourselves in a state of profound disorientation. This is the thesis Latour puts forth in Down to Earth: Politics in the New Climatic Regime. According to Latour, we’ve become hostages to an “epistemological delirium” resulting from the breakdown of principles that had organized modern reality. “Humanity has been deprived of the common framework for ‘becoming modern,’” he asserts. It’s increasingly difficult to believe that globalized markets, “development,” and consumerism lead to universal prosperity. “Epistemological delirium” refers directly to challenges we face in coping with the gradual collapse of what has served as our default worldview. For decades, modernization signified progress, gains, innovation, and civilizational development – an escape from provincialism and rigid traditions represented by local communities, whether rural or marginalized within a single urban center. Locality has been judged backward and premodern – a mere stepping stone on the path to a fully marketized, progressive, and cosmopolitan global village.

The concept of the commons necessitates citizens redefining the assumptions of classical economics (market rationality, individualism, homo economicus) by showcasing how cooperation manifests at the local-community level. Through collective action, we begin to create a community of purpose. This aspect is emphasized by the economist Mariana Mazzucato, who highlights its power in addressing global challenges from climate change and healthcare systems to the growing disparity in access to new technologies. Also noteworthy is widespread political disillusionment, which pushes citizens into the hands of populists. As Mazzucato writes in “For the Common Good” on the Project Syndicate site::

The common good is an objective to be reached together through collective intelligence and sharing of benefits. It builds on the idea of the commons, but goes further by focusing on how to design the investment, innovation, and collaboration needed to reach a shared objective.

It would be naive to claim that the concept of the commons will overthrow capitalism’s regime of private ownership. Most likely, no single economic-management structure will supplant conventional economics. Yet collective practices offer a solution to the problem diagnosed by Latour. “Epistemological delirium” drives us toward civic escapism, a retreat into the realm of privacy, exacerbated further by the way politics is communicated, which is telegraphic and almost abstract. On the other hand, protesting against a local river’s polluter or organizing a community fair is a tangible encounter with something real: a community of care that helps forge connections, awakening the weary, disillusioned citizen from their daze. Commoning advocates for human solidarity and encourages mutual care for one another, constituting the essence of common goods.

Sources: