Science

The 2-Million-Year-Old Skeleton Mystery: Who Was This Ancestor?

09 February 2026

Contemporary popular culture has been dominated by two archetypes: superheroes and antiheroes. While it might seem that the latter are losing popularity, their constant presence in Western pop culture remains an undeniable fact. Has the antihero become the new hero in the reality of neoliberal capitalism? And is their existence truly coming to an end?

Walter White from Breaking Bad, Lisbeth Salander from Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy, and John Constantine, the protagonist of the Hellblazer comic series, are just a few figures in the collective imagination of the Western world that have been etched as antiheroes. Although in recent years we have observed signs of fatigue with the proverbial bad boys, who during the pandemic gave way to protagonists of “cozy fiction,” antiheroes continue to fascinate us.

This thesis is confirmed by the series The Boys, which has gained a legion of devoted fans in recent years. The popularity of Amazon’s production, a deconstruction of the classic superhero narrative, proves that antiheroes still have their place on screens and in the pages of books or comics. Tracing the evolution of pop culture over the past decade or so reveals that contemporary antiheroes differ significantly from their “older brothers.” What is the nature of this difference?

“Antihero” is a nebulous concept, difficult to define. As Piotr Stasiewicz demonstrates in his monograph Between Worlds: Intertextuality and Postmodernism in Fantasy Literature, contemporary dictionary entries offer conflicting definitions of this term. An antihero may be described as someone who lacks heroism. Alternatively, it may refer to the embodied antithesis of traits typically associated with heroes that Western culture values positively (such as courage, nobility, self-sacrifice…).

This type of character is sometimes confused with the villain, the typical hero’s adversary. At times, these figures are difficult to distinguish unequivocally, as in the case of the Joker – Batman’s antagonist and super-criminal from the DC universe, who in Todd Phillips’ film adaptation was not portrayed as an unambiguously evil character. The antihero of contemporary pop culture is most often a morally ambiguous individual, constantly balancing on the edge of good and evil, functioning in a world where traditional values have become blurred. However, such characters are much older than modern cinema or television, with roots reaching deep into the past. Who, then, are the ancestors of Dr. House and Don Draper?

We recommend: Blood, Guts, and Blushes. The Allure of True Crime Series and Podcasts

Among the progenitors of contemporary antiheroes, researchers often include canonical figures from European literature, starting with Orlando Furioso and Don Quixote, through the heroes of Romantic literature, and ending with the protagonists of 20th-century American realist novels.

As Michał Januszkiewicz argues in his article “In the Horizon of Modernity: Antihero as a Concept of Literary Anthropology,” the contemporary antihero originates from Russian Romantic literature. Its prototype was the figure of the “superfluous man” (Russian: лишний человек, literally: unnecessary man), embodied by characters such as Alexander Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin or Grigory Alexandrovich Pechorin – the protagonist of Mikhail Lermontov’s novel A Hero of Our Time (1838-1840).

The typical “hero” of Russian and Western European Romantic literature is a world-weary fatalist, deliberately making himself and others unhappy, convinced of the meaninglessness of existence. The creation of literary characters at that time reflected the generational experience of young writers of the era. Unlike their fathers, participants in the Napoleonic Wars, they perceived themselves as a generation “born too late” and deprived of the opportunity to perform heroic deeds.

The experience of 20th-century historical cataclysms – both World Wars, the Great Depression, and the birth of totalitarian regimes – deepened the process of de-heroization in Western culture that began in the 19th century. The rich gallery of antiheroes was then joined by protagonists of noir novels and films and the literature of the “lost generation” – those affected by the trauma of World War I. As Piotr Stasiewicz notes, the model hero of American culture in the 1920s and 1930s became the embittered and cynical detective in the vein of Philip Marlowe from Raymond Chandler’s novels. He fights evil alone and is guided by a peculiarly conceived morality that distinguishes him from the depraved criminals and corrupt law enforcers he encounters.

According to the researcher, the development of the antiheroic trend in 20th-century culture was a result of the crisis of values that had long been the foundation of Western culture. These examples show that the antiheroes of the 19th and 20th centuries were children of social, cultural, and economic shocks that both creators and consumers of culture grappled with. The birth of the antihero can also be linked to changes in the philosophical discourse of modernity, the discovery of individualism, and doubt in the meaning of acting for the collective. Are the protagonists of contemporary culture also echoes of similar experiences and disappointments?

We recommend: Brain After Death. What Happens to Us During Dying

In a video published on TheTake YouTube channel, Susanna McCollough and Debra Minoff presented the evolution of the antihero trope in contemporary cinema and television. The authors argue that over the past decade or so, we have seen the dominance of two generations of antiheroes, which can be classified analogously to the development of the Web as 1.0 and 2.0.

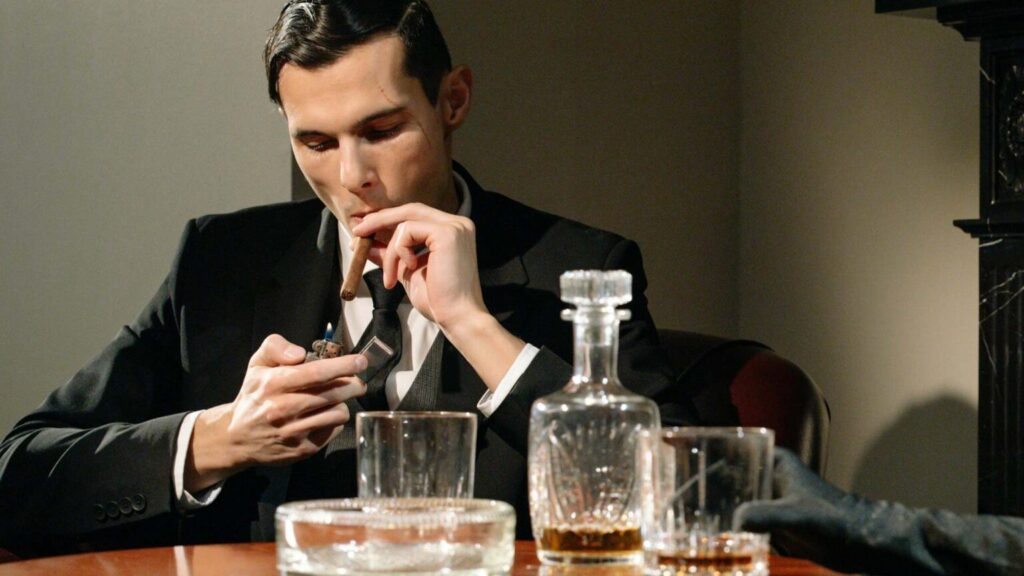

The first group includes protagonists of Western pop culture who celebrated media triumphs in the first decade of the 21st century. Antiheroes 1.0 are predominantly heterosexual men whose behavior can be described – using a euphemism – as morally ambiguous. They are characterized by above-average intelligence and aversion to social conventions, which arouses both controversy and fascination. The latter is further intensified by the aura of mystery that surrounds them. Like the protagonists of Romantic poet George Byron’s works, antiheroes 1.0 such as Dr. Gregory House, Walter White, or Don Draper from Mad Men grapple with their past, which the audience gradually discovers as the plot develops.

McCollough and Minoff point out that the popularity of such characters was closely tied to the evolution of contemporary television and the birth of new-generation series that pushed the previously known boundaries of depicting sex and violence on the small screen. The ambiguous protagonists and dark aesthetics of these productions served as a portal allowing viewers to imaginatively experience the forbidden and “dark” side of reality, which – in the relatively peaceful times of the early century – seemed particularly alluring.

The creators of TheTake argue that in recent years we have witnessed an evolution of the antihero trope, with women and people of color increasingly taking on morally ambiguous roles. While type 1.0 was characterized by moral ambiguity and the “magnetic” charm of an evil genius, the new antihero figure is often no longer presented as a role model – a character we should emulate in real life. Creators of popular recent productions such as BoJack Horseman or Fleabag try to dissuade viewers from identifying with the antihero and encourage critical judgment of their actions.

Contemporary pop culture, McCollough and Minoff argue, thus attempts to show that our misdeeds will not be erased simply because we have decided to apologize and become better people. This issue is perfectly illustrated by the story of the titular protagonist of Netflix’s animated series BoJack Horseman, a former star of a fictional popular 90s sitcom. The horse-man (the series’ world is full of semi-anthropomorphic characters) tries in every way to regain his former viewer recognition. He is selfish and irresponsible, and his ill-considered actions cause suffering to those close to him. The final episodes of the series clearly show that the harm done will forever remain a part of BoJack’s and his friends’ reality.

Although the authors’ reflections are accurate in many respects, it is important to emphasize the arbitrariness of their typology. Antiheroes 2.0 often appear to us as mirror reflections of ourselves. An example here is the character of Fleabag from the series of the same name. The protagonist played by Phoebe Waller-Bridge is in many ways unsympathetic. Nevertheless, many of us can empathize with her and understand that her behavior is the result of experienced traumas. On the other hand, we are not always inclined to succumb to the charm of “bad boys,” that is, antiheroes 1.0. Does not Walter White, dispassionately watching Jesse Pinkman’s girlfriend die from an overdose, evoke antipathy in us? These examples show that the antihero still eludes simple classifications.

Does the transformation of the antihero trope indicate that we have stopped believing in the possibility of rectifying wrongs and started perceiving reality in unequivocally dark colors? It seems that this matter is much more complex. The popularity of antiheroes 2.0 shows that we still recognize the complexity of the world and people, but we no longer want to accept moral relativism and desire to call evil by its name. The evolution of contemporary fiction heroes allows hope that after an era of dark narratives, reflection on the ethical determinants of our behavior will become the new dominant in popular culture. The aforementioned productions demonstrate that such an “ethical turn” does not have to be associated with boredom and didactic clichés.

Translation: Klaudia Tarasiewicz

Read the text in Polish: Antybohaterowie w popkulturze. Daleko im do herosów, a jednak przyciągają do siebie widzów i czytelników