Science

Earth 2.0 Discovered? The Fascinating—and Freezing—Reality of Our Newest Neighbor

06 February 2026

With AI becoming ever more widespread, is human labor set to become redundant in the near future? Or will people simply have less work to complete? Bartłomiej Brach, Doctor of Management Science and lecturer at the University of Warsaw, talks to Katarzyna Sankowska-Nazarewicz about ways of enhancing our sense of purpose in a world where machines are gaining in numbers.

Can you imagine a world where humans no longer have to work?

No, this is a utopian vision. What’s more, such a vision is incredibly destructive for humans, as our DNA has an encoded need to influence reality. We also expect to see the results of our endeavors. And the most difficult and often most rewarding things we can achieve when we organize ourselves into large groups. That is why I find it hard to imagine that one day people will start finding work unattractive or start shying away from it.

What if there are no jobs for anyone to do? The film After Work by Erik Gandini discusses the example of Kuwait, where as many as 20 people are employed to do a single person’s job. They come to work just to be present. They walk around or hang out in what they call the ‘staff storage room.’

Dostoevsky wrote that the easiest way to drive a man insane is to give him a job in which he digs a ditch during the day and fills it in the evening. These Kuwaitis are asked to dig such ditches. They are damaged mentally by having to fake their usefulness and use their energy in some absurd exercise. One of the protagonists and a ‘superfluous worker’ explains at one point that his financial situation is fine, but he is tired of not growing as a person. In my view, these people are quickly traveling towards Dostoevsky’s notion of insanity.

In his film, Gandini showed yet another example of madness. We’re talking about South Korea and the government’s ‘computer shutdown program.’ The initiative aims to stop the culture of overtime by switching off the computers at the end of the working day. Or the United States, where every year people relinquish more than 500 million hours of leave for fear of losing their jobs. He interlaces these themes with the prospect of artificial intelligence turning the labor market upside down at any moment.

I am not afraid of this particular vision. To date, all milestones connected to technological advancement have shown two things – first of all, they have always generated feelings of panic related to the replacement of workers by machines. In reality, human labor was needed in greater quantities each time.

This is especially evident when we look at the example of the online revolution in the 1990s. Many people said at the time: there would be no more need for people who gather knowledge or create content for other media, as everything would be available online. It will be a tsunami, a whole new order. Of course, some companies had to fold, and some people had to look for new jobs, but the events did not lead to the closure of entire sectors of the economy or cause structural unemployment.

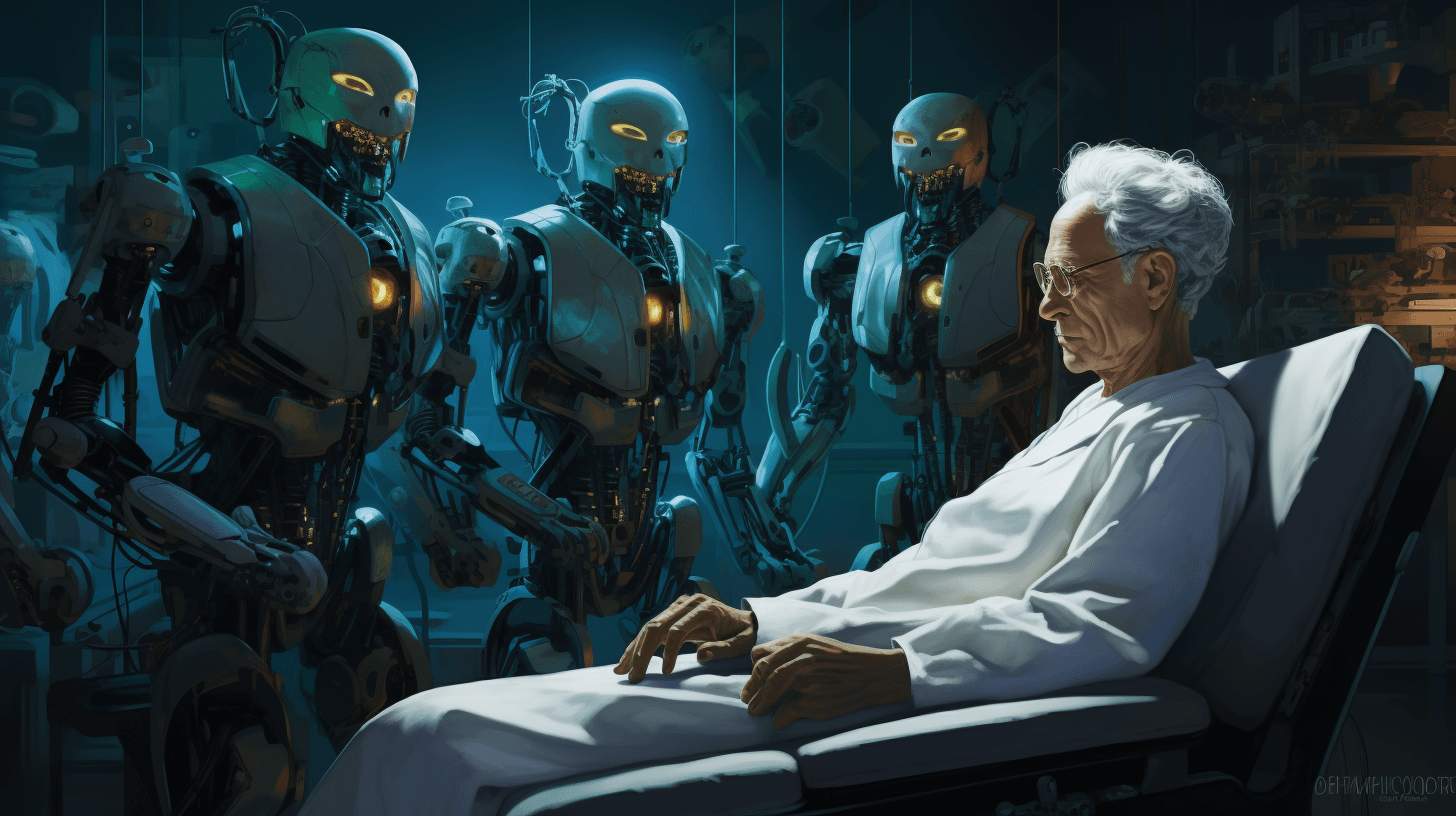

Secondly, it is evident that more and more work is needed that can be exclusively performed by humans. The care sector is a perfect example. It is difficult to imagine an elderly person being cared for by a machine, even if such a machine is multifunctional and able to conduct a conversation. The value of the human touch, eye contact and everything that a human connection brings seems irreplaceable to me.

It would be difficult to disagree with this opinion. Opinions are divided, however, when it comes to the impending technological revolution. Daniel Susskind, author of A World Without Work, believes that the second wave of artificial intelligence is set to make the labor market of the future a historically unprecedented place. He argues that machines no longer need to reason the way people do in order to perform tasks that were, until recently, beyond their reach. He explains machines’ way of thinking based on games in which both Deep Blue and AlphaGo programs were victorious over their human counterparts.

We need to remember that working for a large company is not a game of Go or Chess. Even if an algorithm is able to perform calculations faster than us, put together a presentation more efficiently or complete an Excel sheet, does this mean that our work will be expendable? Or, to put it another way: does an employee only prepare Excel sheets as part of their post? Even the most advanced algorithm will not substitute that employee in all the remaining tasks, such as making important business decisions, organizing teamwork or ensuring communication between various departments.

I find Microsoft’s definition of AI, i.e. copilot, as the closest to the truth. I think it’s highly unlikely that AI will take control over work from beginning to end. AI will become our second pilot who will be able to perform specific tasks for us or provide us with hints on how to solve problems. And we will still act as the captain of the aircraft.

You may also like:

It has to be said, however, that some companies are wholeheartedly engaging in automation. One example is Amazon.

I agree, but I don’t consider a situation in which most companies start resembling Amazon in the near future, at least to some small degree, as very probable. The reason for this is the fact that AI algorithms work well as long as they can draw upon high-quality data. Amazon is investing huge amounts of money to collect data relating to the purchasing process, customer service, warehouse inventories and so on. All this, however, is very costly. This is why I think Amazon and a few of its ilk will function as ‘AI islands,’ while most companies will struggle with basic challenges for the foreseeable future. I know many businesses that are considered the cream of the Polish economy but which have problems generating data other than simple information on sales. Data relating to other areas of the company are either incomplete, out of date or incompatible with other data.

Also, when assuming – purely hypothetically – a situation in which someone wants to transform a company into a second Amazon, we still have to consider the social resistance that may arise when some of the lowest-skilled workers lose their jobs.

Perhaps there would be no protests if they were offered universal basic income (UBI)? What is the purpose of these pilot programs?

There are several reasons for this. People can invest this money in developing their own skills and improving their qualifications. Having such a financial cushion, people may find it easier to take up jobs they have previously steered clear of because these jobs did not pay that well despite being more suited to what they wanted to do professionally. There is also a sizable group of people who are willing or able to work only part-time. This program is designed to allow them to take on part-time work and feel that they can still make a living.

Of course, one motivation is to prepare for a situation in which the actual algorithmization of work will lead to structural unemployment and then universal basic income will be a stabilizing mechanism in the event of a considerable crisis. The income will then counteract any civil unrest.

Which use of universal basic income sounds most realistic to you?

I agree that UBI may be useful as a safety net; however, today it may be much more helpful in encouraging the vocational activity of some parts of society and in instilling the belief that work is something more than what someone is willing to pay for it.

However, studies conducted by the National Bureau of Economic Research show that the long-term effects of UBI could be very destructive. Economists have said that the UBI pilot programs are too short to assess their genuine impact on our approach to work. For this reason, they studied the behavior of lottery winners over a period of five years. When these amounts were divided, the amount of money due per month was roughly the same as that paid out under the UBI program. The difference was that these people had a different perspective – the money was not enough to last them two years but secured them a fairly comfortable future. The economists conducting the survey noted that these individuals did not learn new skills and chose less demanding and lower-paid jobs. According to the researchers, such an approach has the most pronounced impact on the youngest, who are in the process of building their professional lives.

I understand these arguments. It seems to me, however, that the greatest difficulty lies in the fact that we are constantly looking at a world that is not yet a reality and is, therefore, difficult to evaluate. Many people said, for example, that the pilot UBI programs would fail to have a positive effect and that their beneficiaries would ‘eat through’ the money and become dependent on the state. Almost all studies conducted to date have proved to the contrary – that these people have become more active professionally, with their sense of agency and security also receiving a boost.

As we mentioned at the beginning, another thing I believe is that people will always have the basic need to generate value. Most people will continue working, as work is a vital activity that allows us to have an impact on reality.

And even if some people decide to be less active in the labor market and take their involvement elsewhere, for example, by volunteering in their housing community or organizing activities for children, I don’t think that this is a bad thing because any such activity adds value to society.

It is possible that there will also be a third group with no plans of doing anything, so the value of that group’s social impact will be limited. However, the high value of the first and second group will balance out the third group’s personal and professional inactivity.

The second group seems to resemble Daniel Susskind’s idea of ‘conditional’ universal basic income, as part of which we would receive remuneration in return for work performed for the benefit of the community. Such a solution would aim to give people a sense of purpose in a world with less and less work available.

This idea would prove very challenging to implement, as how would we establish that a particular activity is a sufficient involvement? Would we consider helping a neighbor in her garden as valuable work? I think it is, but someone may have a different opinion. And how would we know that such assistance has indeed been provided? Would we have to log in to a special app? Enter times we worked in the garden into an Excel spreadsheet? Following this line of thinking, we are in danger of waking up in a world described by Shoshana Zuboff, an American philosopher and social psychologist. In such a surveillance society, everyone can be screened and controlled on the basis of generated data.

The vision which emerges consists of individuals at risk of having things taken away from them because we decide that their contribution to society is insufficient. Such a vision frightens me, and I wouldn’t want to see it put into action.

I am thinking about our children who will be starting their first jobs in a decade or so. How will they find this new reality? I imagine they will need a variety of skills and strong internal motivation to rapidly adapt to change. Meanwhile, our schools continue to teach children to answer questions according to the answer key and intimidate them with low grades.

I agree. We are still stuck in a Bismarckian educational system, although the times we live in are no longer Bismarckian. What we can do as parents is, first of all, to change the questions we ask our children. This is because questions can also be incredibly formative.

Let’s look at a classic question we all remember from our childhood: “What would you like to do when you grow up?” programs children to think about work in terms of specific professions. The coming years foretell that we need to change the optics, and the question should be rephrased to: “What kind of person would you like to be?” This is because even if this ‘Susskindian’ scenario comes true – in which the market becomes unpredictable, and we have to change jobs frequently because our current post is taken over by machines – the question of what values we hold dear will still be relevant.

We recommend:

Science

06 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny