Science

Have We Been Lied to for Years? The New Food Pyramid Divides Doctors

09 March 2026

The concept of hibernation is rooted in both nature and human imagination, as well as science. We know that some animals, like bears, can sleep through winter and awaken in spring. However, a few months of dormancy are nothing compared to 40,000 years of hibernation. Scientists have discovered an organism that was nearly dead for such an astonishing period, yet managed to return to life.

As early as the 18th century, researchers began to understand organism hibernation as a physiological process. They analyzed the mechanisms of this phenomenon in mammals, inspiring further experiments and even attempts to apply this mechanism to humans. So far, they haven’t achieved this, but other organisms show an incredible ability to survive. One such case is an astonishing discovery in the Siberian permafrost.

A German team, led by Dr. Philipp Schiffer from the University of Cologne, found a worm there that had survived frozen for approximately 46,000 years. Scientists wanted to understand how this organism managed to survive such a long time in a dormant state.

Siberia is a land of vast expanses of permafrost – soil and sediments that remain frozen for at least two consecutive years. In some places, the layer of icy ground reaches hundreds of meters deep, and low temperatures perfectly preserve everything trapped within it.

For humans, such conditions are extreme, but it is also a true treasure trove for scientists. An icy time capsule where remnants of animals, and even living organisms from thousands of years ago, can be found.

Recommended: Rethinking Plastic: More Recycling or Reduced Consumption?

The discovered worm belongs to a group of animals that can enter a state of cryptobiosis. This extraordinary ability allows organisms to almost completely halt their vital functions to survive extreme conditions. You can compare this to pressing “pause” on a remote control – the organism goes dormant, waiting for better times.

When conditions become favorable again – for example, water appears – it “comes back to life” as if nothing happened. It’s a bit like dried fruit rehydrating and regaining its original structure when placed in water.

In the state of organism hibernation, almost no metabolic processes occur, yet they can survive conditions that would normally be lethal. Scientists have long studied cryptobiosis in tardigrades and brine shrimp. These remarkable animals can “freeze” their vital functions and wait for the environment to become hospitable again.

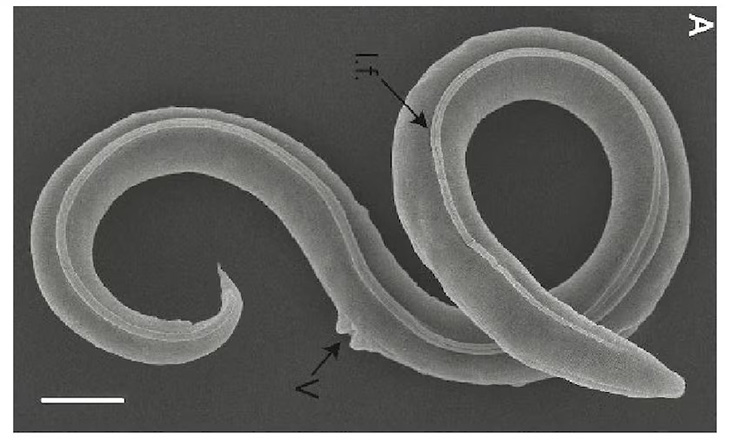

Researchers determined that the discovered worm is a new species of nematode, named Panagrolaimus kolymaensis, which had never before been described in scientific literature.

It was unearthed from a depth of approximately 40 meters, where icy cold prevailed. It was precisely these conditions that allowed it to survive in dormancy for thousands of years. When it reached the laboratory, it revived, began to function normally, and even produced offspring.

Nematodes typically live 1-2 months, but thanks to organism hibernation, this worm extended its lifespan to an absurd 46,000 years. Now, experts want to find out how this is possible. Perhaps its body produces special cell-stabilizing molecules that protect it from damage even in extreme conditions.

“No one suspected that this process could last thousands of years – 40,000 years, or perhaps even longer. It’s simply incredible that life can restart after such a long time,” said Dr. Schiffer in an interview with Earth.com.

To determine what makes this worm so unique, scientists sequenced its genome. It turned out to have genetic similarities to Caenorhabditis elegans – a popular nematode used in laboratory research. This means that both species may share a certain “survival gene set” that allows them to enter a state of cryptobiosis. A similar mechanism is observed in tardigrades, also known as “water bears.”

In 2017, NASA discovered that these microscopic creatures can survive in space – they cope with extreme cold, radiation, and drastic temperature fluctuations. This makes them among the most resilient organisms on Earth.

They live practically everywhere – from Himalayan glaciers to ocean floors, from humid rainforests to urban rooftops. They are literally ubiquitous and almost indestructible.

Read more: Where Ethics Meets Science: Which Part of the Brain Controls Morality?

Read this article in Polish: Zadziwiająca hibernacja nicienia z Syberii. Przeżył aż 46 tys. lat