Humanism

Water, Fire, and Integers: How Ancient Architects of Thought Deciphered the Cosmos

22 February 2026

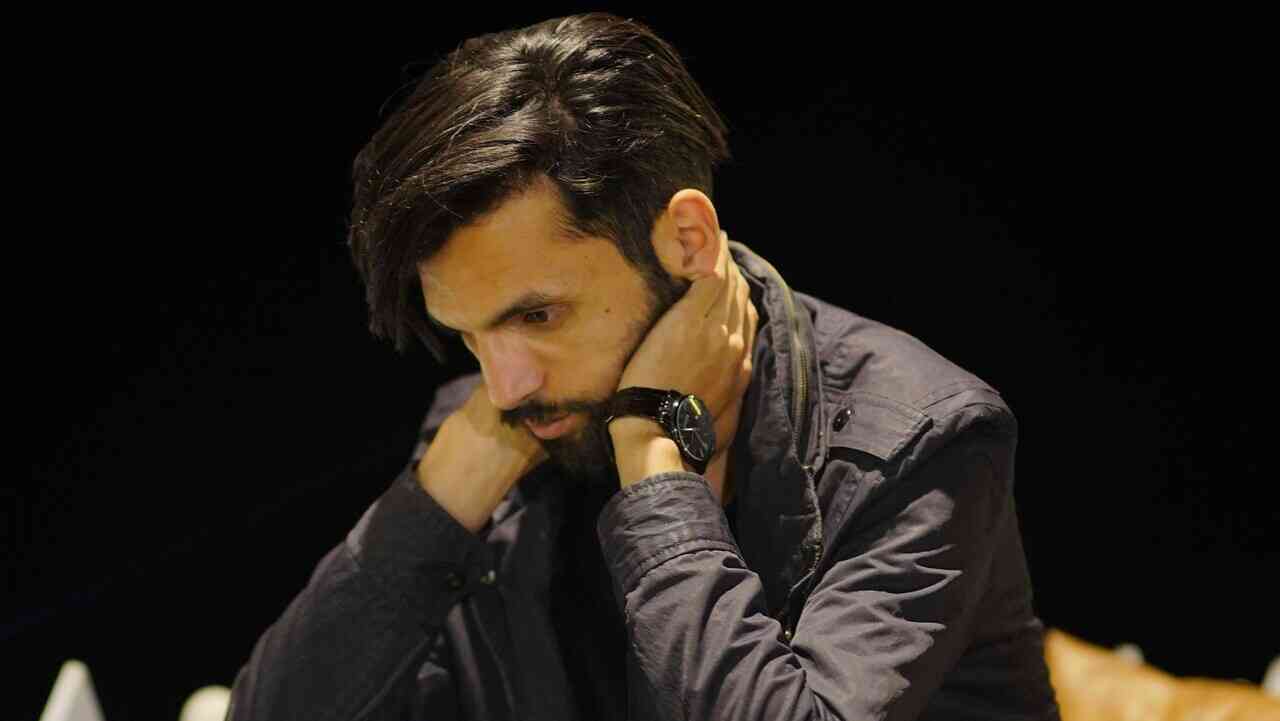

The January premiere of The Master and Margarita directed by Mikhail Lokshin attracted crowds of viewers to Russian cinemas. In the opinion of critics, the production is one of the best adaptations of Bulgakov's novel. However, the film has become a target of Kremlin propagandists, calling for a halt to screenings and punishment of the filmmakers. How is it possible that in a country where culture became the weapon of war, anti-regime film screenings were allowed?

Among filmmakers, there is a belief that Bulgakov’s magnum opus mysteriously opposes bringing its characters to the screen. This constatation initially concerned the latest adaptation of The Master and Margarita, the work on which began in 2018. Financial troubles, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic, caused the project to fall apart at the scenario stage.

The realization of the idea was resumed after a few years. Lokshin involved Russian and European actors in the film. Universal Pictures studio was responsible for international distribution. Shooting was completed in 2021 with financial support from the Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation. Russia’s armed attack on Ukraine had a direct impact on the resignation of foreign partners from participation in the production. The director officially condemned the war and left for the United States in protest. The film was shelved for almost two years, confirming the thesis of the curse hanging over screen adaptations of the novel.

Given the anti-war attitude of Lokshin, as well as the exceptionally present sense of the Master and Margarita, the consent to the distribution of the film is an unprecedented event in Putin’s Russia. However, storm clouds have gathered over the director. The voices of criticism from the Z-patriots, among whom there are also people of art and culture, are not silent. The situation in which the filmmaker finds himself resembles the hero’s story from Bulgakov’s novel. “All the things that were in the film, in a sense, happened in life,” the creator said in an interview.

We recommend: Mental Slavery: Who Shapes European Culture?

Lokshin’s future in Russia is in question. There are voices calling for a criminal case for him for discrediting the Russian army and spreading false information about a “special military operation” in Ukraine. The issue of the director’s American citizenship is also raised, which may result in him being given the status of a foreign agent (ru иностранный агент) and/or being included in the list of terrorists and extremists.

With the help of the “Law on Foreign Agents in the Russian Federation,” the Kremlin effectively eliminates the contesting creators of culture. The infamous list included, for example, a best-selling crime writer Boris Akunin. The writer’s case was investigated for justifying terrorism, which he commented on social media: “The terrorists considered me a terrorist.” His books have been withdrawn from sale. Contracts signed with Russian publishers were canceled.

Ivan Vyrypaev, a playwright and theater director living in Poland, was sentenced to eight years in prison for fakes about the Russian army. A few months later, a similar sentence was passed against Dmitry Glukhovsky, the author of the popular novel series Metro. In turn, film and theater director Kirill Serebrennikov, accused of embezzlement of state money, received an exceptionally mild sentence: Three years of suspended imprisonment. During the trial, he was under house arrest and then dismissed from the position of director of the Gogol Centre.

The black list of agents, terrorists and extremists is being successively supplied. Some cultural activists who criticize the political course taken by the Russian president. In interviews and social media, they declare anti-war attitudes and protest against censorship and lack of creative freedom. Many of them have chosen emigration, for example, the famous diva of the Russian stage Alla Pugacheva. The silence of the media on her 75th birthday proves that the artist fell out of the Kremlin’s favor.

Russian culture has been divided into two parts. “Those who praise war and Putin receive generous confitures from the authorities. Those who criticize the war and Putin are being displaced, harassed, sentenced and separated from the Russian audience,” Anna Labushewska comments. Musicians are demanded to engage and publicly support Moscow’s imperial aspirations. In return, they can give concerts, and record albums and profit from being a Russian star. Since the beginning of the armed conflict in Ukraine, the singer Grigory Leps has accepted the direction of foreign policy set by the president. The vocalist does not complain about the lack of work. He performs at rallies in support of a “special military operation,” gives interviews, and recently has been preparing a stadium concert to celebrate his 62nd birthday.

After the scandalous “almost naked party” in one of Moscow’s clubs, where famous figures from the world of show business appeared, the number of artists ready to participate in Z-campaigns in support of the war increased. Dima Bilan, the winner of the 53rd Eurovision Song Contest, recently returned from Donbas, where he performed for Russian soldiers. Earlier, another well-known participant of the December party, Filip Kirkorow, decided to play a concert in the war zone. Most of the stars publicly apologized for attending the event, which was perceived as part of Putin’s game with unruly celebrities. These public acts of repentance testify to humility toward the authorities. They arise from the fear of losing privileges, fees and, in extreme cases, freedom.

We recommend: Pop Tradition: Can Popular Culture Replace the Canon?

The Kremlin began to take an interest in cultural institutions long before 2022. There have been changes in directorial positions, sometimes interference with the repertoire of theaters, blocking the financing of specific film projects. But refusals to cast actors because of their political attitude, removal of names from theatrical posters, unjustified dismissal of artists with many years of experience, and cancelation of performances and exhibitions have not taken place on such a scale since the times of the Soviet Union. Culture has once again begun to serve ideology. Censorship has become a widespread phenomenon, and the reactivation of the infamous tradition of denunciations keeps society in check.

Many artists chose to flee after being intimidated and vilified for their strong opposition to the war. Russian propaganda depicts leaving the country as a betrayal. Cooperation with Western cultural institutions is sufficient reason to be considered a foreign agent or accused of extremism. The remaining opponents of the current authorities in the country prefer to remain silent or act without publicity.

Russophobia is a term used by propaganda media to eliminate Russian culture from European heritage. Meanwhile, in Putin’s state, the “castration” of culture takes place daily. Analogies to the times described by Bulgakov impose themselves. This makes the Kremlin’s approval of the screening of Lokshin’s film all the more surprising. The latest adaptation of the novel will not change the Russian Federation, just as the publication of The Master and Margarita did not contribute to significant changes in the Soviet Union. One can only hope that the film will trigger critical thinking among the representatives of Generation Z, which is fed with the idea of the great-power role of the Russian state.

Translation: Marcin Brański

Humanism

22 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny