Science

The Monk Who Saw the Future: Did an 11th-Century Benedictine Beat Astronomers?

17 February 2026

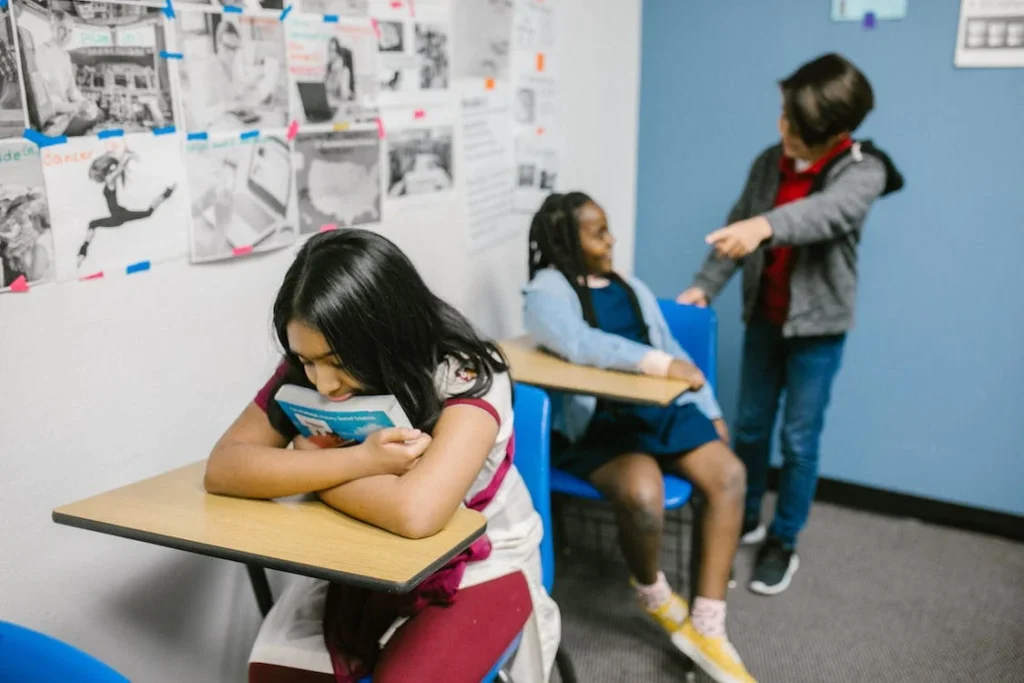

The need for belonging is as fundamental to human beings as the need for safety and personal growth. While there is a desire to distinguish ourselves, our primary concern is to be recognized and accepted by others. Unfortunately, this recognition is not always achievable, and for children and adolescents, its absence can be particularly agonizing. This struggle frequently leads to a lack of self-acceptance, which can, in turn, manifest as self-destructive behavior, contributing to the rising incidence of suicide attempts.

Effectively addressing these challenges, which include mitigating the impact of parents’ deficiencies in providing essential support to their children, necessitates the implementation of inclusive education. This approach demands organized efforts and supportive measures for student development to guarantee equal educational opportunities for all. A fundamental requirement for enabling the participation of all students in school life is to ensure comprehensive accessibility. This encompasses students with disabilities as well as those without proper medical documentation and assessments. It also includes individuals who may encounter difficulties due to specific physical or psychological conditions, differing cultural or social backgrounds, or experiences associated with migration.

The Polish education system urgently needs specific modifications to ensure it provides an inclusive educational model for all students. There is a critical need for specialists in schools who have the capacity and availability for direct interaction with each student requiring personalized support. This is a crucial measure to combat the escalating trend of suicides among children and adolescents, as direct interaction with a child is often the most potent deterrent against thoughts of self-harm.

Feeling different due to various special needs is a common experience among children and adolescents. Michał Cichy, a journalist with “Gazeta Wyborcza,” shared a poignant recollection of his childhood in a series of articles titled “Live Better”:

“At the age of five, I had recurring nightmares: each side of my bed harbored a different monster. At the head of the bed, a gigantic dog devoured me alive. On the wall side, a corrugated vacuum cleaner hose engulfed me. On the room side, a lamp suspended from the ceiling lowered cords that lifted me up to the ceiling and deposited me on a scalding radiator high above the floor, from which I couldn’t jump down. However, the most terrifying side was the foot of the bed. A small, furry creature, which I referred to as a kingfisher, emerged from behind the curtain, and I knew it was followed by a massive monster. I never actually saw it, but the mere anticipation of its approach was enough to jolt me awake.”

This statement can be seen as a special metaphor for the experiences of students who come to school with a myriad of different experiences in interacting with the world. Some may have visual impairments, others may have hearing difficulties or be hypersensitive to sounds and the presence of others, and furthermore, others may misinterpret the gestures and words directed at them. Sometimes, children with below-average intellectual abilities enter the institution and react in extremely unusual ways: with shouting, aggression, or with excessive and uncontrolled movements.

In essence, for the average teacher, the optimal student is one who understands what is happening and acts according to accepted principles. It is assumed that if this is not the case, it is best for the student to sit to the side and not disturb others. Unfortunately, a significant portion of students not only do not want to be sidelined from what is happening in the class but also, additionally, cannot adapt to the norms that seem obvious to teachers. They are simply different and require different, specialized treatment. The reasons for their differences or special needs can vary widely; let us examine some of them.

An increasing number of children with a history of migration are enrolling in schools. The concept of the world as a global village, introduced by Canadian philosopher Marshall McLuhan, highlighted that all global inhabitants are linked by the same set of information. Nowadays, this connection may be less evident through television or computers, yet it is unmistakably apparent on our streets and in our schools with the growing presence of newcomers from different parts of the world. In addition to experiencing migration, these children often live under the shadow of trauma, violence, displacement, or war.

Children impacted by migration find themselves in an environment that is, to varying degrees, unfamiliar. Their arrival in a new living situation presents a host of novel experiences and emotions. These range from cultural shifts, such as a new language, customs, and behavioral norms, to deeply personal changes observed in physical, biological, economic, or social aspects. The breaking of social support networks, anxiety for people and sometimes animals left behind, significantly affect children’s mental well-being. This is exacerbated by feelings of isolation, potential stigmatization and secondary victimization, and the absence of support from individuals previously considered dependable. The daily conduct of new peers and inappropriate adult behavior—excessively protective, sympathetic, ultimately negatively distinguishing—are undeniably impactful. There is also the influence of social media used by the community the new migrant student is joining, often featuring envious and disdainful prejudices that lead to condemnation and stigmatization. Additionally, the prevalent youth trend of sharing images of assault victims and violent acts, underlining a peculiar entitlement to violence or even boasting about an assault, is a noteworthy factor. Other challenges for teenagers may include their appearance, economic status, ability to engage in extracurricular activities, use of a specific language code that emphasizes shared experiences, or a distinctive way of interpreting the world, characteristic of their new environment.

An expanding demographic of rising concern includes young individuals who, feeling marginalized, resort to suicide attempts. Schools are now populated with students who have endured the challenges of isolation due to recent pandemic restrictions. A notable portion of these young people are the younger siblings of the “snowflake” generation. It is important to note that “snowflakes” are predominantly self-centered individuals, highly susceptible to criticism and any form of failure. Owing to their “helicopter” parents, snowflake generation children not only exhibit significant irrationality but are also increasingly responding to a lack of anticipated opportunities with self-harm or even attempts at self-destruction. “Helicopter” parents are those who, being proximate to their children’s academic lives, are always prepared to intervene. Consequently, their approach largely involves assuming full decision-making power and even responsibility for their children.

Numerous factors contribute to the increasing sense of exclusion within the snowflake generation. One significant factor is the mentioned parental educational incompetence that hinders children from fully participating in their own lives. Additionally, social media has become a crucial influence for many young individuals, dictating their worldview, values, and rejections. It seemingly determines one’s perception, level of appreciation, and instances of deprivation of belonging to a chosen, yet unpredictable and generally merciless virtual group.

It is crucial to understand that the feeling of exclusion is foundational to one’s self-perception. A young person’s existence hinges on the recognition and unconditional acceptance by others. Previously, concrete relationships, shared conversations, events, appearances, and reactions to others’ actions directly impacted our sense of connection with others. However, in today’s virtual reality, our self-image and others’ perceptions of us are paramount. Consequently, any critical comment or even fabricated information can lead to a sense of exclusion from a specific community. In some cases, this can even drive children to desire self-exclusion from their own lives.

The data is alarming. In January 2023, the Polish National Police reported 856 suicide attempts that did not result in death. The majority of these attempts were made by adolescents between the ages of 13 and 18. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that for every documented suicide attempt, there are about 100-200 incidents that go unreported. The numbers highlight the continuation of a disturbing trend that has been increasingly evident over the past several years.

Mental crises, including those that lead to suicidal thoughts, are widespread and notably affect children and adolescents more severely. Why is this the case? Monika Kamińska from the Empowering Children Foundation notes that a significant number of children in Poland dread facing each new day, while adults often dismiss their feelings with comments like, “I had real problems at your age.”

Lucyna Kicińska, co-author of the report “Suicidal Behavior Among Children and Adolescents,” emphasizes the need for increased funding for psychological and pedagogical support in schools by the Ministry of Education and Science. However, the ministry mainly suggests financing, among other things, speech therapy and group psychological and pedagogical assistance. According to the quoted suicidologist, this is not an appropriate response to a child’s emotional crisis. To genuinely help students in crisis, school specialists simply need employment that enables them to conduct an adequate number of individual consultations. Direct contact and conversation with a child contemplating suicide are often highlighted as factors that ultimately dissuade them from following through with their intentions.

Inclusive education is about structuring the school environment to foster optimal self-development and self-fulfillment for all students, including those with special needs. This approach views the natural diversity of students as an asset rather than a barrier to achieving set goals. Children’s needs can vary widely, including differences in pace of work, interests, talents, personality traits, cognitive abilities, physical fitness, social and cultural experiences, worldviews, values, and crises. A growing crisis among children is the need for support when feeling excluded, which can sometimes lead to suicidal attempts.

To provide effective support, schools need specialists and dedicated time and space for direct interaction with each student requiring individualized help. Grandiose announcements or empty slogans about support are insufficient. Humans, as social beings, have three fundamental needs: belonging, recognition, and acceptance. When a child falls outside the satisfaction of these needs, they may lose their will to live. Usually, they first rebel against others, but it can only be a matter of time before they turn against themselves.

Science

17 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny