Science

Have We Been Lied to for Years? The New Food Pyramid Divides Doctors

09 March 2026

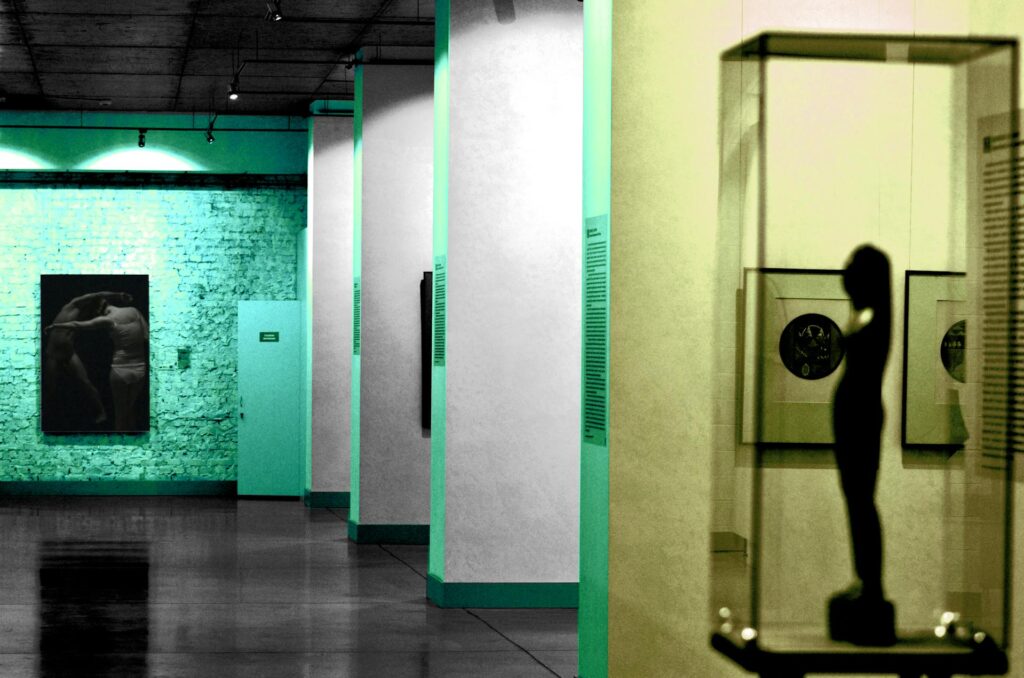

Art remains a bastion of freedom, a realm where the imposition of personal interpretations on others is frowned upon. While discussions about perceptions are welcome, the ultimate judgment on a piece’s appeal lies with its audience. Art continues to provoke potent emotions – a sign of its undiminished impact.

Debates over taste may seem futile, but exploring viewers’ reactions that shape their relationship with art is instructive. Instant admiration and rapid rejection coexist, highlighting the subjective nature of art appreciation. The essence of experiencing art hinges on whether it resonates with us. Anna Matuchniak-Krasuska from the Institute of Sociology at the University of Łódź emphasizes the longevity of our emotional responses to art: they can be fleeting, but they can also be long-lasting.

In both aesthetics and psychoanalysis, it is the artists who are credited with expressing internal experiences, not the observers. The artists convey emotions; the observers experience them – this delineation is crucial.

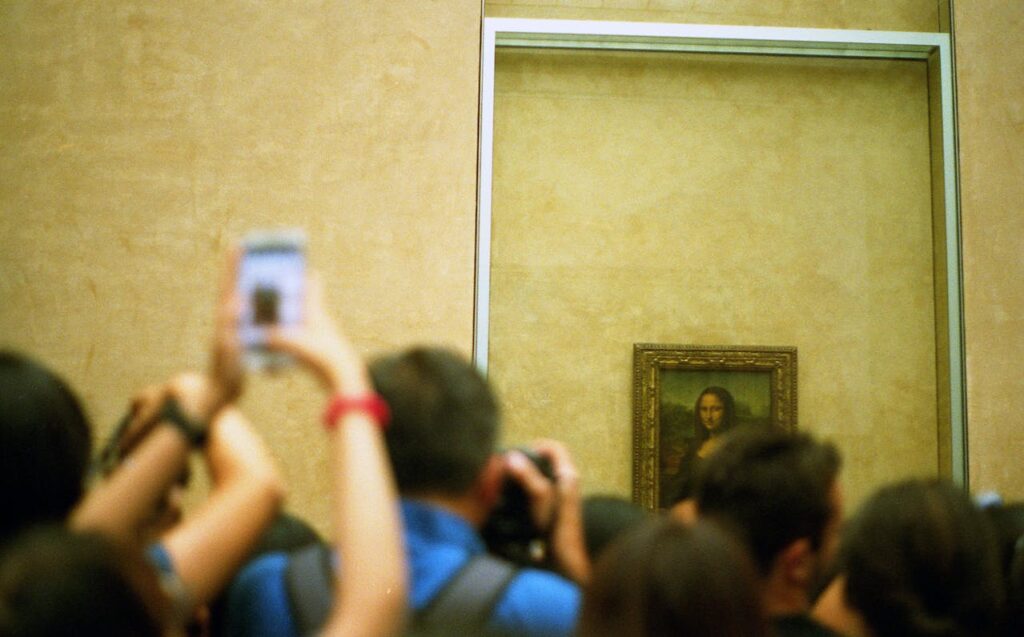

In a work of art, both content and form convey emotions. A painting engages us as a holistic piece of art; we observe the scene on the canvas and strive to interpret its content, even in abstract pieces. Typically, avant-garde works, those divergent from our accustomed styles, or creations by lesser-known artists do not find favor. This may suggest an intuitive trust in societal tastes, ingrained in us from our school years. Consequently, the acclaim of mass culture’s creations is not surprising.Hence, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers and Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa attract universal admiration. The value of these acknowledged masterpieces is seldom questioned. At most, we might discuss observations such as the unexpectedly modest dimensions of these famous works. Interestingly, mass culture creations, often deemed kitsch, also garner widespread approval. Positive reactions are elicited not only by high art but also by seemingly kitschy pieces, like sentimental depictions of deer in rutting season, which resonate with many viewers.

A positive reception of art typically pertains to works by renowned artists entrenched in global classics, notably from the Italian Renaissance, French Impressionism, or 19th-century Polish Realism. Esteemed figures such as Leonardo da Vinci, Monet, Renoir, and Matejko exemplify this elite group. Their artworks are admired both for their subject matter and their portrayal. Art history reveals that we are most fond of portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes that depict action.

The aesthetic experience is a phased process. Władysław Tatarkiewicz highlighted two key stages: imagination and concentration, both shaped by the artwork’s nature and the viewer’s predispositions. Similarly, Roman Ingarden described the progression from an initial emotional response to a conscious intellectual analysis, culminating in the viewer’s judgment of the artwork. Aesthetic experience, then, comprises pure emotion, receptive engagement, and evaluative assessment. The accompanying thoughts can persist in us for hours, with the memory of the experience lasting even longer.

Viewers often expect a visceral “impression” from a painting, seeking to feel fear, curiosity, satisfaction, or disgust. The composition and color palette are analyzed first, followed by the technique. The aesthetic experience, however, is fleeting, it is like a single second that determines the artwork’s reception. Leopold Staff’s poem captures this, describing the lyrical subject suspended “between the lips and the edge of the cup.” The poet’s imagery aptly illustrates the elusive nature of this process. Our feelings and perceptions of art remain enigmatic, often surprising even to ourselves. We think we understand our preferences, yet our choices can still astonish us.

We recommend: Subliminal Messages in Art: Are the Artist and the Work a Singular Whole?

Negative emotions are frequently stirred by avant-garde art, which remains unfamiliar to many. Artistic novelties may find acceptance only among a select group of intellectual and artistic elites. As outlined in the book Emotions, Culture, and Social Life, edited by Piotr Binder, the wider society, including its educated members, often exercises the privilege of disliking and not understanding such art. It is noteworthy that abstract and thus deformative paintings caused an aesthetic shock for most people a century ago. Even Picasso required time to gain acceptance from the general public.

Contemporary art typically provokes negative emotions and is formally rejected. The subjects depicted are considered ugly, and the situations are obscene. Furthermore, contemporary themes may offend not just aesthetic sensibilities but also religious and social norms.

Another aspect is the fascination with art due to its economic value, leading to paintings being collected and acquired at private auctions. Often, we purchase artworks without fully understanding their content. Sometimes, we appreciate art without delving into its subtler aspects. Consider medieval religious art: does anyone pay attention to the rich symbolism of gestures depicted in paintings from that era? For instance, a figure with a hand on the cheek signifies pain, clasped hands represent despair, and crossed arms with a turned head denote deceit. Iconic gestures in art, such as the divine finger in Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” or biblical scenes, provoke strong emotions. The enigmatic smile of the Mona Lisa has spurred numerous analyses in the sociology of art.

Psychologists point out that people express emotions not only through facial expressions but also through gestures and speech. Expressing emotions is one aspect; recognizing them is another. Ostensibly, ugliness and beauty are concepts that mutually imply each other. Typically, ugliness is understood as the opposite of beauty. Art researchers have noted that by creating abstract works, artists have stripped art of content. In return, audiences do not respect their intentions and often avoid such works altogether. Moreover, they declare that such works do not evoke any emotions in them. Thus, the fundamental role of art, which is to stir emotions, diminishes.

We must also remember that few domains enjoy as much freedom as art. This freedom applies to both creation and reception. Art exists and should remain within the realm of freedom. We cannot impose our ways of interpretation on others; we can discuss them, but whether a piece resonates with others is for the audience to decide. One thing is clear: art still elicits strong emotions. And may it always do so.

Translation: Klaudia Tarasiewicz

Polish version: Zachwyt i oburzenie, czyli o emocjach w sztuce i ich przeżywaniu