Science

Is Water in Space the Rule, Not the Exception? The Mystery of Planetary Birth

24 February 2026

For just a few hours, a single, distant star shone brighter than ever before. That brief window was all it took for an international team of experts to achieve something never before accomplished: the direct weighing of free-floating planets drifting through the void, proving that these "rogue" worlds are a reality of our galaxy.

In the vastness of space, there are worlds that do not orbit any sun. Known as free-floating planets—or rogue planets—these objects are cold, dark, and notoriously difficult to spot. Until now, astronomers could only find traces of them, but their exact mass remained a mystery.

Now, an international team of astronomers, with the key participation of scientists from the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw, has for the first time in history directly “weighed” a free-floating planet. This planetary object was discovered wandering alone through the Milky Way, entirely unattached to any star.

“This is the ‘discovery of the decade,’ comparable to the first documented exoplanets in the 1990s,”

– says Professor Andrzej Udalski, leader of the OGLE (The Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) project.

“Astronomers finally have definitive proof that these types of objects exist throughout the Universe.”

The study detailing these findings was recently published in the prestigious journal Science.

Typically, planets like Earth or Saturn orbit a star that provides light and heat. However, during the chaotic birth of a planetary system, some can be ejected—often due to gravitational collisions with larger neighbors. These free-floating planets then roam the galaxy in isolation. Theoretical models suggest there could be billions of them in the Milky Way, perhaps even outnumbering the planets that remain with their stars.

Previously, astronomers had identified potential candidates for such worlds. However, without an accurate mass measurement, they couldn’t be certain whether these were actual planets or much heavier objects, such as brown dwarfs.

On May 3, 2024, telescopes on Earth noticed a distant star near the center of the Milky Way briefly brightening for only a few hours. This phenomenon is known as gravitational microlensing.

Simply put: the gravity of a planet passing in front of a distant star acts like a magnifying glass. It bends the starlight, making it appear brighter. The duration of this flash depends on mass—lightweight planets cause very short bursts.

The event was recorded by the OGLE telescopes (located at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile) and the KMTNet network. However, it is difficult to determine mass and distance from the flash alone—a lightweight planet nearby produces the same effect as a massive one far away.

This is where the Gaia satellite—a European Space Agency (ESA) telescope located 1 million miles from Earth—played a vital role. Gaia also recorded the flash, but it saw the event two hours later than observers on Earth.

This “stereo vision,” or microlensing parallax, allowed scientists to calculate both the distance and the mass of the object.

The verdict is in. The planet’s mass is 0.22 times that of Jupiter, or approximately 70 times the mass of Earth. This makes it comparable in size to Saturn. The planet is solitary. It has no host star within a radius of more than 20 astronomical units (1 AU = 93 million miles, the distance between Earth and the Sun).

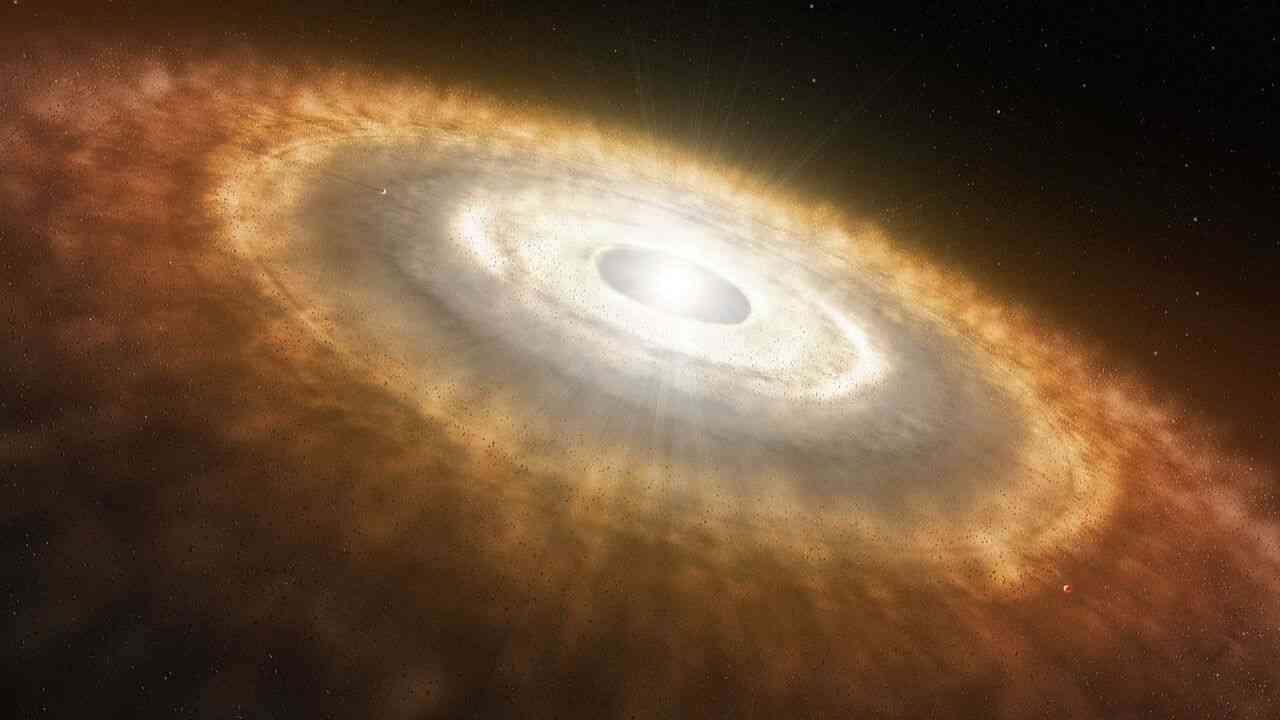

It likely originated within a protoplanetary disk around a star, much like a typical planet. Later, gravitational forces violently ejected it into interstellar space.

The OGLE project, led by Professor Andrzej Udalski from the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Warsaw, monitors millions of stars across the sky. The Polish team provided the crucial ground-based data and the comprehensive analysis that made this discovery possible.

This measurement marks the first direct mass confirmation of a rogue world, proving they are indeed planetary in nature. Much like the discovery of the first exoplanets 30 years ago, this opens a brand-new chapter in our understanding of the cosmos.

The discovery paves the way for future missions. In 2026, NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will launch, followed by the Earth 2.0 mission in 2028. Both will be hunting for more free-floating planets, but they will be standing on the shoulders of the pioneers who caught that single flash on a night in May.

Read this article in Polish: Jedna noc, jeden błysk i wielkie odkrycie. Historyczny sukces Polaków

Science

24 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny