Science

Hidden Depths: Thousands of Unknown Viruses Found in the Dragon Hole

16 February 2026

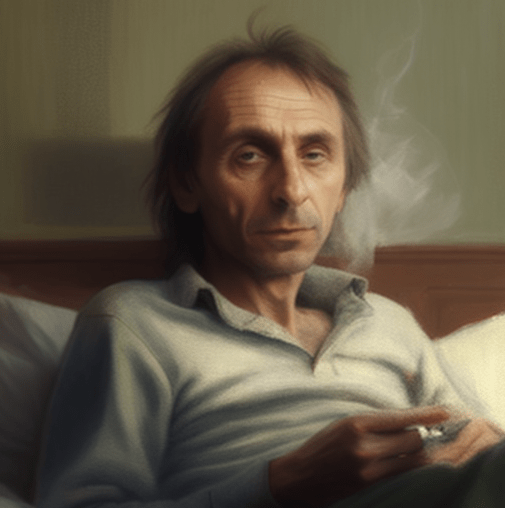

Michel Houellebecq is among the fiercest critics of contemporary society. While in recent years other French writers have won the Nobel Prize for literature – J.M.G. Le Clézio, Patrick Modiano, and Anne Ernaux – Houellebecq is today the country’s most popular living writer.

At the beginning of his career, Houellebecq gained the regard of left-leaning critics through clearly expressing his disapproval of neoliberal individualism as it blighted Western Europe. Today, the same critics regard him as a “prophet of the populist right” along the lines of Steve Bannon, not the intellectual name-checked at rallies for Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of La France Insoumise, the left-wing populist party. What has become typical of Houellebecq, as he stepped with mounting boldness into the role of provocateur and trickster, is the increasing radicalization of his views in a conservative-reactionary direction. Despite this, he remains an author who is difficult to pigeonhole, if only due to his sensitivity and excellent ear for social discourse.

Late last year, the magazine Front Populaire published an extensive conversation between Houellebecq and the philosopher Michel Onfray. It has provoked an uproar across the political spectrum, even among those on the far right, where Houellebecq’s antics had been approved to date.

In the interview’s first part, he focused on alarming demographic indicators before arriving smoothly at the conclusion that the Great Replacement conspiracy theory, in which white Europeans are being replaced by Muslims, was not just a theory but a fact. Furthermore, he portrayed Muslims as a threat to the security of the non-Muslim French: “The wish of the French natives is not that Muslims assimilate, but that they stop stealing from them and attacking them; or, another solution, that they leave.”

Houellebecq also threatened readers with a “Bataclan in reverse” targeted at Muslims, in an allusion to the terrorist attack on a Paris concert venue on November 13, 2015.

Even by Houellebecq’s lofty standards of discourse, recent statements have gone far beyond standard critiques of religion commonly accepted in secular France. Therefore, the Grand Mosque of Paris filed an official court complaint that was then withdrawn after a meeting between the two litigants. The writer has officially changed his position on French Muslims and expressed his “deep regret for the words spoken.”

It wasn’t the first time Houellbecq’s derogatory remarks about Islam and its followers have wound up in court. In 2002, the justice system found Houellebecq guilty of inciting religious and racial hatred after he called Islam a “stupid religion” and described the Qur’an as “badly written” (the latter allegation was dismissed). Another controversy arose in 2015 with the release of Submission, the plot of which revolves around a Muslim political party turning France into an Islamic state.

In January of this year, a trailer for Dutch filmmaker Stefan Ruitenbeek’s coming release circulated on the Internet, in which the world-famous writer kisses and hugs a young woman. The clip is from the feature film Kirac 27,’ which includes a sex scene between Houellebecq and a Dutch sex worker. Following the trailer’s release, the writer complained in the media that the film had damaged his reputation. He also claimed the contract between him and the director was void as he was under the influence of alcohol while signing it.

A complaint was duly filed in Dutch court, in which Houellebecq demanded “an immediate halt to the attacks on his person” through “withdrawing the trailer from platforms and social networks.” He even proceeded to try his case in court to annul the contract on the grounds mentioned above. The Amsterdam court did not agree with the “wronged” Frenchman and allowed the film to be released. Its premiere has yet to be announced.

Read also:

Every few months, Houellebecq appears in the media with a new article or gives an interview, his statements almost always going viral and eliciting emotional reactions. During the pandemic, he shared his thoughts on the epidemiological situation. In a letter to France Inter, a public radio broadcaster, he wrote:

We will not wake up after the quarantine to a brand new world. I do not believe in declarations that nothing will be as it was before. It will be the same world, only a little bit worse.

In 2019, Houellebecq published an essay in Harper’s titled “Donald Trump Is a Good President,” sharing his views on the current state of US aviation – “the fact is, however, that the Americans never knew how to carry out a proper bombing” – and taunting the EU and NATO: “France should leave NATO, although this may turn out to be unnecessary if NATO disappears due to lack of budget for its operation, which would mean one less hassle […]. The European Union was not invented to be a democracy; its purpose was exactly the opposite.” He then continues his praise: “President Trump was elected to defend the interests of American workers […] All in all, [President Trump] seems to be one of the best presidents to have happened to America.”

One good summary of the discussion so far may be the recent comment by Jean-Philippe Domecq, a columnist for Le Monde, who stated: “what will remain of Michel Houellebecq will not be his works, but the fact that so much will have been said about him.”

For years, Houellebecq has managed to maintain a top position among bestselling authors in his country. In 2019, nearly 400,000 people bought his novel Serotonin. It was fourth on sales list, right behind the star of the thriller genre, Guillaume Musso, and The Adventures of Asterix’s thirty-eight volume. Last year, bookmakers tipped him as the leading contender for the Nobel Prize but the award went to his compatriot Annie Ernaux.

Houellebecq’s prose is filled with nostalgia for a great France in the midst of industrial progress and full employment – for the era of les trente glorieuses. The Glorious Thirty are the years from the end of the Second World War to the 1973 oil crisis. Each of his characters reckons with this bygone era in their own way. In Serotonin (2019), Florent-Claude dreams of France being restored to its condition before feminists, environmentalists, secular liberals, and EU bureaucrats ruined it.

According to Houellebecq, the outbreak of the pandemic is the fulfillment of some of his earlier predictions, mainly from his book The Possibility of an Island, in which the narrative axis focuses on the gradual disappearance of physical human contact. However, as early as in his first book, Whatever, in 1994, he has been writing about changes to come:

Before our eyes, the world is becoming more uniform, the means of telecommunications are being developed, the interiors of homes are being filled up with modern furnishing. Human relationships are gradually becoming impossible, which, incidentally, is reducing the number of stories of which a lifetime is made up. In this way, the face of death is slowly manifesting in all its splendour.

Houellebecq’s Whatever

Long before Thomas Piketty and his Capital in the 21st Century, he constructs protagonists who become aware of the declining ethos of the specularized (that is, a bourgeoisie bidding farewell to the dream of social advancement). The writer acknowledges his class position. In an interview with French television, he acknowledged: “Whether I like it or not, I am a part of France that is voting for Macron because I am too rich to vote for Le Pen or Mélenchon.”

On the other hand, Houellebecq shamelessly mocks the heritage of French intellectuals. He ridicules the derealization of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and goes on to point out Malraux’s involvement in political disputes. In contrast, he compares the writing of Bourdieu or Baudrillard to a clique of old shoemakers. It’s not so much a set of critical epithets as of populist snapshots that, in Houellebecq’s own eyes, bring him closer to an imagined common folk.

The central figure in this article describes himself as a monarchist and a Catholic who gazes fondly upon the community-building legacy of communism: “Communism has a less global character than Christianity, but it was not that bad. It was not anomic, but rather joyful. If I were nostalgic, this is what I would regret.”

For some, Houellebecq has become the epitome of a secular prophet. The conservative magazine National Review went a step further, calling the prophetic parts of the author’s prose “The Houellebecqian Moments.” These are presumed to identify events in which society is “beginning to catch up” with ideas he’s conveyed in his prose.

Houellebecq isn’t only a reactionary, he’s also a critic of present-day capitalism. He loathes the permissiveness touted by liberalism, as well as the homogeneity of today’s consumer culture. With his writing, he contributes to a long tradition of European political pessimism:

So, if I now reflect on the situation of the West, taking into account those two criteria which, because of my intellectual experience, I consider fundamental, namely demography and religion, it is clear that I come to the same conclusions as Spengler: The West is in a state of well advanced decline.

Houellebecq’s literature can free us from primitive optimisms served up by free-market society and its institutions, which constantly assure us that they are able to satisfy our every need and turn us into whomever we want to be. On the other hand, Houellbecq’s attitude is a classic case of “good ol’ days ideology,” further explored by Lisa K. Libby and Richard P. Eibach in an article:

As people get older, they begin to confuse the changes taking place in themselves with changes in the world around them, and changes in the world with moral decline – this is where the illusion of the good old days stems from.

—“Ideology of the Good Old Days: Exaggerated Perceptions of Moral Decline and Conservative Politics”

What is most interesting about Houellbecq’s story is that he can be taken as a serious political guide both by right-wing columnists and by squat anarchists ardent in their aversion to the establishment and capitalism. Supporters of other political options may see him for what he really is: a writer expressing the various problems of France and Europe with precision and intelligence without offering any potential solutions in return.