Science

Lost on the Moon for 60 Years: AI Joins the Search

23 February 2026

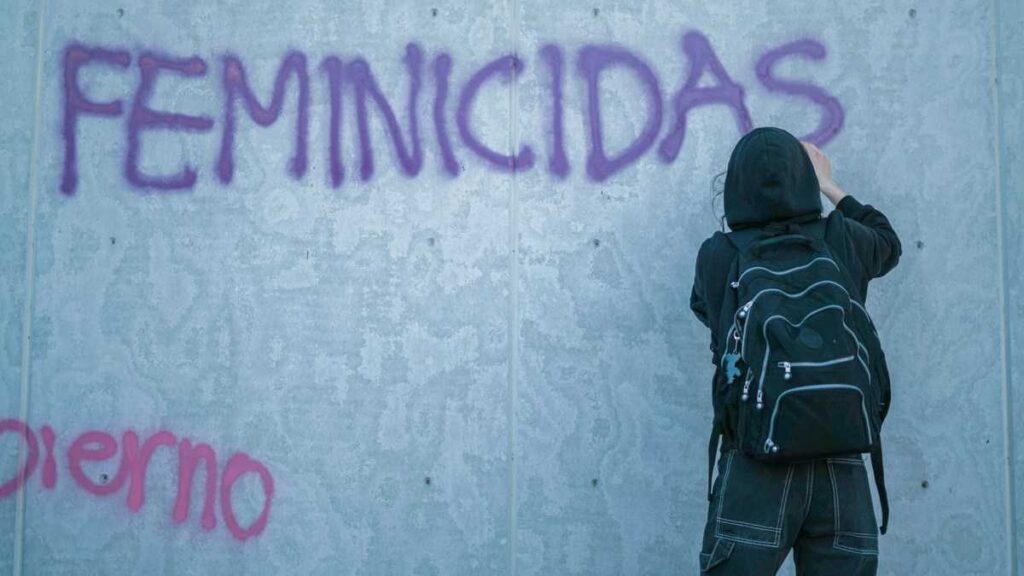

Why is Latin America such a dangerous place for women? The problem extends far beyond general crime rates. Local machismo culture undoubtedly plays a major role. We analyze this phenomenon and examine the controversial femicide laws that grant women special status. Why do these regulations—and attempts to change them—spark such intense emotion, especially amidst the ongoing Latin America Femicide crisis?

This is a grave matter, literally concerning life and death. Latin America remains a particularly vulnerable region for women. Formally, women do not possess fewer rights than men. Yet, in practice, women’s safety is constantly compromised. From Mexico to Chile, the criminal practice of femicide—the killing of women based on their gender—is rampant. Countries in Central and South America and the Caribbean top the infamous statistics, numbers one would typically expect to see in reports from a war front. In the decade starting in 2000, over 5,000 women and girls were murdered in Guatemala in this context. In 2023 alone, Honduras recorded a total of 386 femicides. Last year, Mexican records included nearly 800 such cases. Nevertheless, this represents a downward trend, as nearly a thousand murders were recorded three years earlier. Many cases, however, went unreported. Argentina registered close to 270 femicides in 2024, following over 300 the year before.

The term “femicide” (from the Latin) was first used to describe the killing of a woman by Irish writer John Corry in the early 19th century. The term saw a revival in the 1970s, gradually acquiring various definitions. Feminist author Diana Russell narrowed it to the practice of “the killing of females by males because they are female.” In her theory, she used the term female, referring generally to the female sex, thus including the murder of girls and infants. According to another definition, “the term ‘femicide’ refers to the murders of women, regardless of motive.”

Indeed, the reasons for femicide can vary. They most often stem from the deeply ingrained machismo culture in Latin America. This culture fosters a sense of pathologically conceived masculine pride and strength; it ensures men’s primacy in most areas of life. Such a belief inherently permits full domination over women.

This assumed superiority tolerates no competition. Furthermore, men often view any deviation from this rule as justification for committing a so-called “honor killing.” From the perspective of machismo culture, this action cleanses a man’s honor, for example, after a woman cheats on him.

This warped belief system allows some regions to operate on the premise that a woman can be killed with impunity. Exacerbating this is the region’s extraordinary level of general criminality. Human trafficking flourishes, and nearly all Latin American countries struggle with drug cartel wars. However, when a man joins a gang, he often brings his family—his wife, daughter, or sister—into the “dowry,” allowing the gang to do as it pleases with them.

Criminality does not arise in a vacuum. Many families live in poverty, and girls, starting from their teenage years, seek work in American-owned factories opening up in places like Mexico. Interestingly, in such cases, young women can pose direct competition to men. Mechanized production does not require exceptional strength, and employers often view female workers as more obedient, disciplined, and cheaper. Sociologists attribute the aggression men direct toward women attempting to compete in the job market, in part, to this factor. This theory explains the grim fame earned by the Mexican city of Juarez.

For decades, this city of about 1.5 million people attracted young women from deep within the provinces, seeking work in various assembly plants (maquiladoras). In the 1990s, approximately 1,500 women were brutally murdered in and around the city. According to sociologists, the underlying cause of the sick aggression in many cases was the desire for revenge against attempts to break the machismo culture. Women who began earning money no longer had to abide by the dictates of their male partners and began to show it ostentatiously, which local men could not tolerate.

Murders and other crimes committed against women in Latin America gradually became almost normalized. The performance—or rather, the sociological experiment—conducted in El Salvador in 2013 by artist Denise E. Reyes Amaya, where she pretended to be a corpse on the street, was highly telling.

Nevertheless, from time to time, the cruelty and senselessness of these murders shocked even indifferent societies. Authorities in individual countries, under pressure from demonstrations, began to review the law. Authorities gradually isolated and criminalized crimes against women committed due to gender, ultimately introducing femicide as a crime that carries a harsher sentence. Costa Rica was the first to change its legislation in 2007, followed by Guatemala a year later. Ultimately, a total of 18 countries in the region followed suit, although some limited their model to murders committed only within marital or partner relationships.

In 2012, under President Cristina Fernández, Argentina joined the countries that reformed their laws. The local penal code imposes life imprisonment for a murderer of a woman if the perpetrator is a man and the crime involves gender-based violence.The scope of the femicide crime covers marital and various forms of partnership relationships, such as engagement or even dating. The law applies to both current and past relationships. Femicide in Argentina also includes murders intended “to cause suffering,” such as killing a child as revenge against the mother.

The current President of Argentina, Javier Milei, referenced these provisions during this year’s economic forum in Davos. He asserted that the law concerning femicide is unnecessary and, moreover, unfair. He invoked the principle of equality before the law. “We are going to remove the provision on the murder of women from the Argentine Penal Code because our administration defends the equality before the law enshrined in the Constitution. No life is worth more than another,” stated the President. His Justice Minister further emphasized that femicide in the penal code “distorts the concept of equality and only seeks privileges, setting one half of the population against the other.”

Javier Milei’s statement provoked street protests, but the President consistently defended his position, arguing that efforts should focus on limiting all forms of violence, not isolating femicides. His administration contends that “the legal system should prioritize efficiency and effectiveness in resolving crime in general, rather than maintaining specific categories that can complicate the judicial process.”

Abolishing the concept of femicide in the penal code is not the only goal of Milei’s conservative administration, just as introducing the femicide provision into the legal system was not the only change that left-wing circles pushed for. The President also seeks the repeal of gender identity laws, which were introduced the same year as the femicide decree. He is also trying to abolish later enacted employment quotas for transvestites, transsexuals, and transgender people, as well as electoral parity and a law introducing mandatory gender-issue training for public sector employees.

The changes and arguments presented by the Milei government did not arise out of thin air. The aforementioned gender identity law, which allows gender designation based solely on personal declaration without regard to biological indicators, has stirred up a lot of controversy.

In this context, the case of Gabriel Fernandez garnered widespread attention. Born male, he was known for brutally treating women he was in a relationship with. Convicted of assault and abuse against his partner, he leveraged the gender identity law. He declared himself a woman and, as “Gabriela,” was incarcerated in a women’s prison. How did this impact the safety of the women imprisoned there? Last year, a female inmate sharing a cell with “Gabriel/Gabriela” reported she had been raped by him, which left-leaning media attempted to frame as a woman raping a woman. The fact that the victim became pregnant after the rape did not deter them.

Quotas for public administration positions are also problematic, as they mandate that “no less than one percent of the total number of jobs be reserved for transgender people.” Ultimately, this suggests that one in every hundred soldiers in the Argentine army should be a transvestite or transsexual. This is a complex aspect of the Latin America Femicide discussion.

The final argument for the Argentine President could also concern the effectiveness of introducing the concept of femicide into the justice system. Does it truly have an effect and deter potential aggressors? According to statistical data, femicide remains the scourge of Latin America. In some countries, such as Brazil, which currently holds the unenviable third place in terms of the number of murders committed against women, the practice has even intensified.

Honduras fares the worst, where the femicide law was passed in 2013, and the current femicide rate per 100,000 women is 7.2. This is nearly 3.5 times higher than the Dominican Republic, which ranks second.

However, can we say that femicide is a problem limited to Latin America? Absolutely not. Machismo culture, regardless of its name, exists in various regions of the world and often results in crime.

In March 2025, the Italian government approved a draft law that introduces the crime of femicide into national law. Convicted perpetrators could face life imprisonment. Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni said in a statement that the bill “provides for aggravating circumstances and stricter penalties for crimes of abuse, stalking, sexual violence, and revenge pornography.” At the same time, however, the conservative government is careful, similar to the Argentine example, not to “throw the baby out with the bathwater” and approaches the gender identity law and LGBT education cautiously. Italian authorities are already being criticized for this, including by the Council of Europe.

Read the original article in Polish: Ameryka Łacińska ma problem. Kobiety nie mogą czuć się bezpiecznie

Science

22 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny