Science

How Did Life Rebound on Earth? The Answer Lies Within the Rocks

23 February 2026

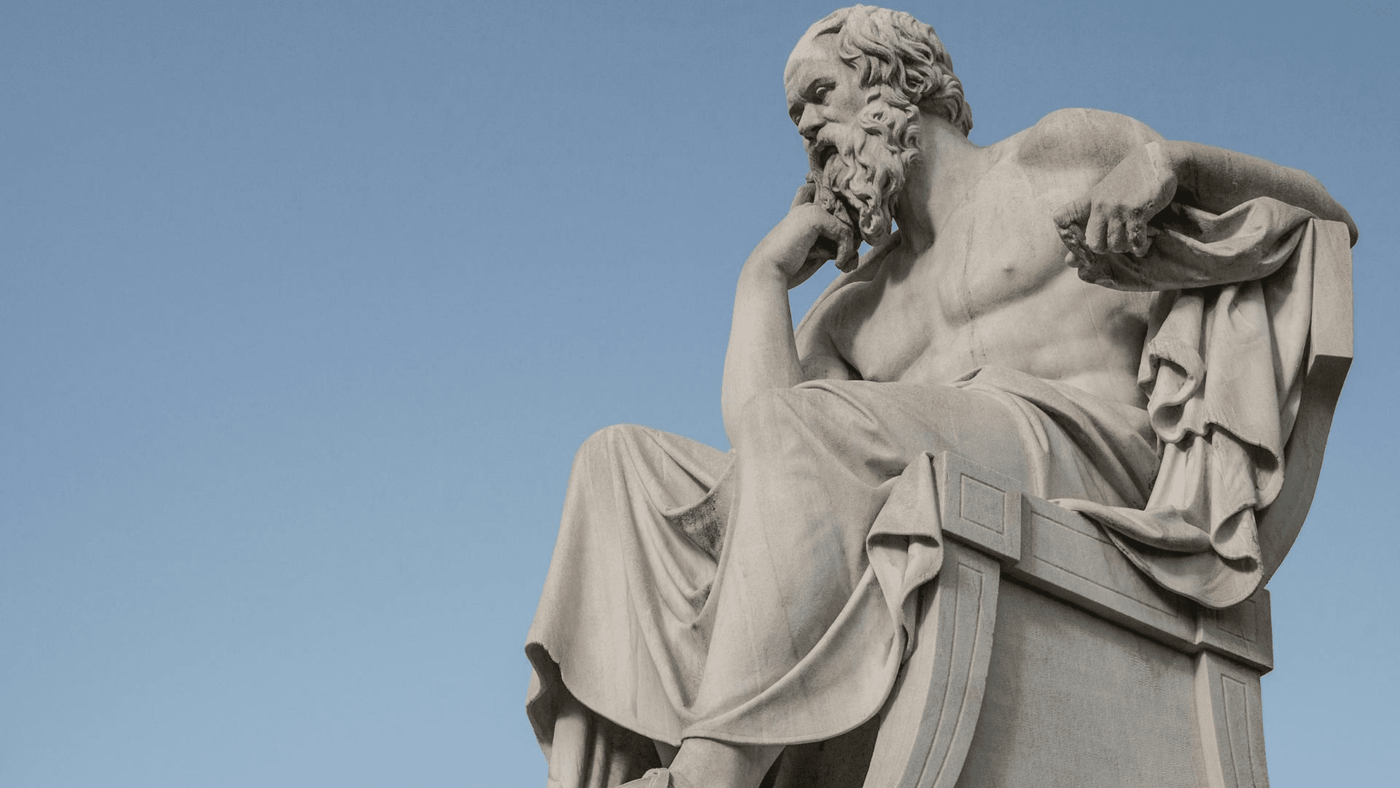

The world is divided into idealists and realists. Their ideals guide the former, and even if they cannot put them into practice, at least they direct themselves toward them. They resemble the fettered people of Plato’s famous cave metaphor, heading toward the sun that illuminates their path. The path itself gives them a sense of meaning and fulfillment. Pragmatists fit into the realists' group, for whom ideals are unimportant because what matters is the reality in which they find themselves and factual data. So what do they look for their happiness in? Do they do better in life than idealists?

To better understand the meaning of the word “pragmatism”, it is worth reaching out for its definition. The Collins Online Dictionary indicates two interpretations. Pragmatism is:

1). “Character or conduct that emphasizes practicality”,

2). “A philosophical movement or system having various forms, but generally stressing practical consequences as constituting the essential criterion in determining meaning, truth, or value”.

The above distinction points to pragmatism, which initially functioned as a philosophical attitude, shaped in the 19th century by at least two American thinkers: Charles Peirce (1839–1914) and William James (1842–1910). They tried to combine theory with practice according to their scientific standpoint. Peirce was a logician by education and treated pragmatism as a method of logical analysis, and his goal was to determine the real meaning of each concept.

James was a psychologist, so his understanding of pragmatism was more focused on processes related to consciousness, especially the workings of our will. Peirce strongly emphasized the importance of human nature — it tends to make man in action guided by the practical consequences of their deeds. On the ground of investigations of both thinkers, the so-called pragmatic conception of truth was then formed, according to which utility, and consequently effectiveness, is the only criterion for the truthfulness of our judgments.

American philosophers only gave the concept of pragmatism a certain shape, and, as it often happens, over time it began to “live its own life.” When it permeated everyday use, it took on a new meaning. In the 21st century, the understanding of pragmatism was reduced to the first of the dictionary definitions quoted earlier.

The modern use of the term “pragmatist” certainly refers to its roots, however, today the word is understandable not only for philosophers. Pragmatists are usually rationalists who approach the world analytically, follow logic, and control their emotions. In determining their subsequent tasks, they are primarily guided by potential results. As interpreted by this group, a practical approach to life is to act effectively and focus on the gains that can be achieved. Assertiveness, diligence, and a large dose of assurance are supposed to lead to success.

Pragmatists usually cope well with stress just because they coldly calculate what is conducive and what makes it difficult to meet an assumed target. Stress, tension, and excessive nervousness are not allies in the practical approach to life, so pragmatists naturally eliminate unfavorable factors. On the one hand, they can impress and motivate others to follow them, but on the other hand, they can arouse distrust and incline people to stay at a distance. Why?

We recommend: Faithfulness to Goodness, Truth, and Beauty: The Need for Idealists Today

For many people, an attitude based on cold calculation and following only the “profitability” of the actions taken, often reinforced by the desire to dominate, raises doubts. Each of us has other cognitive powers, besides reason and thinking, that are also a natural element of human construction and are needed because they serve us for something. Suffice it to recall the thought of Blaise Pascal (1623-1662), who stated:

“Two things teach man about their whole nature: Instinct and experience” (Thoughts).

As one of many philosophers, he also pointed out that intuition, sensitivity and emotions do not always have to lead us astray and be an obstacle to achieving our goals. Unfortunately, pragmatists often lack some freedom and flexibility in thinking and acting, which are eliminated by an analytical approach to the world. More often than other personality types, they are guided by proven patterns and more trust in template prompts than their fantasy and ability to create freely.

This translates into conflicts in relationships with people who think and act according to different criteria than pragmatists. It also contributes to the creation of an image of a person who is closed-minded and convinced that only their approach to the world is right. It is also worth mentioning that pragmatists do not necessarily like novelties, let alone situations in which they would have to take a risk. They can always lose something, and a potential loss simply does not pay off.

Perhaps it will be a cliché to say that – like any other life attitude in life – pragmatism also has pros and cons. An important question in this context seems to be the ethical one: Can a model of action based only on rational premises and a logic of cause and effect lead to happiness? The aforementioned Pascal wrote:

“Imagination cannot make fools wise, but it makes them happy, to the shame of reason, which can only make its chosen ones miserable.”

Pragmatists, rejecting the value of fantasy, imagination, intuition, and all irrational forces in man, somehow reduce themselves to pure rationality, which seems contradictory to the natural human condition. A commonsense approach to reality is undoubtedly a valuable thing and helps many people. It gives a sense of security, an impression of predictability of actions taken, and a certain order in life. But do they not become poorer by something at the same time? Do pragmatics who orient their lives according to the principle:

“I will take only those actions that will lead me to success and at the least cost.”

Can they build successful relationships with other people? Are they able to adopt an attitude based on trust, honesty, and selflessness? These values are not countable and require taking some risks, but they very often bring people happiness. In short, can the orientation of one’s life toward success identified by the balance of profits and losses, give a person a sense of fulfillment?

Perhaps it is worth advising modern pragmatists, to close their eyes for a moment, to pause in their world of calculation, profitability and predictability, and to recall the motto of the great idealist Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), contained The Critique of Practical Reason:

“Two things fill the mind with ever new and increasing admiration and awe, the oftener and more steadily we reflect on them: the starry heavens above and the moral law within.”

Perhaps such reflection will open them to other ways of striving for happiness than those they already know well.

We recommend: From Defeat to Self-Discovery: How Modern Individuals Confront Extreme Situations in the Spirit of Karl Jaspers’ Philosophy

Translation: Marcin Brański

Science

22 February 2026

Humanism

22 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny