Science

Homo sapiens and a Mysterious Human Species: We Have Their Genes

27 June 2025

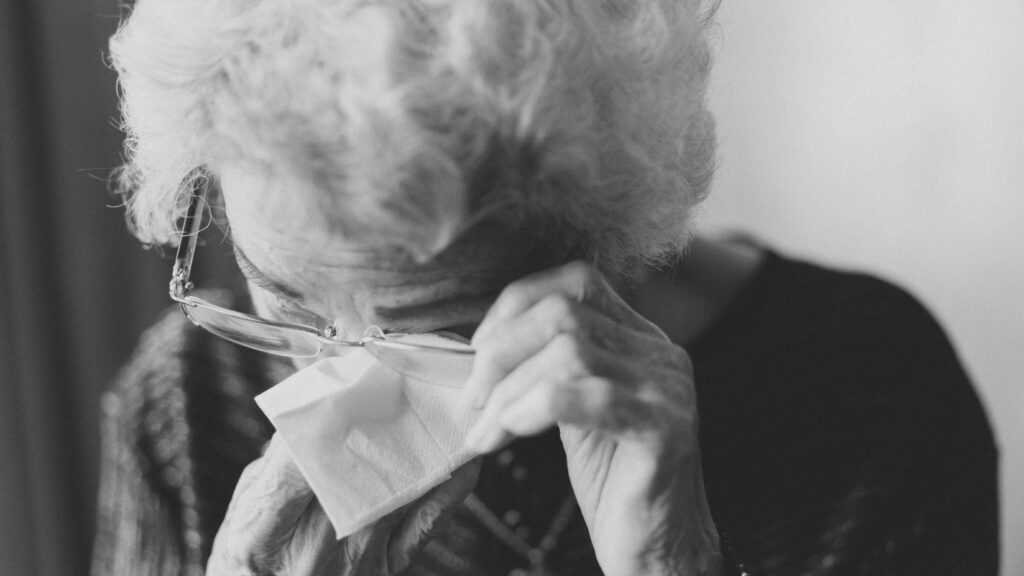

According to statistical data, older people in Poland feel increasingly lonely. They submit to isolation, become depressed, and their health deteriorates. “Seniors need contact and friendship. However, they are not always able to articulate it clearly. Sometimes simple mindfulness to another person is enough to help,” explains Dr. Rafał Bakalarczyk, a social activist and publicist, an expert on older people at the “Senior Hub” Senior Policy Institute.

Anna Bobrowiecka: According to Statistics Poland, one in four people aged 80+ feel lonely and experience a sense of isolation and abandonment. Why is this so? Are they people who have no family?

Dr. Rafał Bakalarczyk: This is a very multidimensional problem. Isolation is understood not only as an objective and easily measurable human situation but also as a subjective feeling. Limited or unsatisfactory contact, regardless of the reasons for this isolation, may also be accompanied by various unpleasant emotions associated with them, such as the feeling of loss or rejection. Moreover, as the Mali Bracia Ubogich (Little Brothers of the Poor) association’s report on the loneliness of people aged 80+ showed, those seniors who feel lonely are more likely to experience a sense of uselessness, a pessimistic view of the world, insecurity and the lack motivation for various social, health and everyday activities.

Thus, isolation is not always simply the effect of being or living alone – although the number of older people living alone is also increasing for various reasons, for example, due to the migration of younger generations (often abroad) and the fact that relative and family ties have been loosening in recent years. The previously common pattern of a vast family network of people who maintain close and regular contact in many cases already ceases to function. These relative networks loosen, sometimes even break. The changes within the immediate family translate into a circle of relationships and potential support for the elderly. It is not only about children and grandchildren, who are statistically born fewer in number but also – and often above all – the (non)presence of a spouse or partner of a given person.

The elderly, especially in more advanced old age, are not infrequently people who are already widowed (this experience is more common among women who live statistically longer). But there are also those – and their number will grow – whose marriages or informal relationships have broken up. Some people have not entered into such relationships at all. As a result of these demographic and relational trends, with each generation entering the old age stage, the scale of experiences such as loneliness and isolation may be increasing.

We recommend: Between Youth and Old Age. The Way We Manage the Aging Process Affects our Quality of Life

Surely, the demographic crisis, especially the increasing reluctance to start a family, will worsen the problem.

Our choices – and sometimes forced circumstances – in earlier years of life have consequences in older age, even if we do not always think about it. However, there are also not uncommon cases of people who have not entered into relationships or have not raised families for reasons beyond their control, against their own needs or dreams. Often there are even health, and social limitations or traumas behind it that make it difficult to enter and maintain relationships. Some people also face rejection or abandonment by loved ones at various stages of their lives, which can also hinder entry into a new, close and permanent relationship. The issue of childlessness is not necessarily a choice or an effect of cultural trends, but a combination of different limitations – for example, due to infertility affecting many people in the prime of life.

To sum up, both the sense of isolation and real loneliness are the effects of very different, contemporary processes within the sphere of relationships, especially (but not only) family relationships, changes in our approach to them, as well as delayed consequences of experiences in various phases of the life cycle also play a role. It is worth looking at this problem from broader, intergenerational perspective. The good news is that recently the topic has started to be raised as a public problem, as evidenced by the report on loneliness published by Instytut Pokolenia (the Generations Institute) some time ago.

The difficulties in question are also known to other countries, but the phenomenon has to be embedded in the Polish socio-cultural context. Satisfaction of emotional and caregiving needs has traditionally been strongly based on the family. In many cases, when family support is absent, broken down, or weakened, other non-family options are still not realistically available for many people. In the case of the elderly, although the immediate family remains the leading source of support (as shown by subsequent editions of the Pol Senior survey), we must look for alternatives that are only slowly emerging to shape and are not widely accessible. Regardless, the use by older people of various theoretically existing forms of integration or social contacts may also be limited by different barriers – social, health or psychological, or access to information.

The scale of senior loneliness “jumped” in 2021 during the pandemic. Did that time worsen the situation, or has this phenomenon been growing steadily for years?

This phenomenon may increase, for reasons we have already mentioned, but the pandemic has also deepened and accelerated this process. Its health and psychosocial consequences have affected us to varying degrees. However, they had an extremely severe impact on older people, due to the specificity of this age group as a risk group, but also the general condition of older people in society.

Even when the lockdowns ended and the restrictions were loosened, these people were often afraid to leave the house anyway. Initially, sometimes they were even discouraged from leaving their homes because of the risk to their health. The distancing was justified by reality and concern but also had unintended side effects. How many seniors, however, have returned at any time to contact with their surroundings and pre-pandemic activities? And whether this inaction was temporary or has turned out permanent.

Here, one would surely have to look at detailed research. It seems to me that unfortunately, many older people who “fell out” of their communities did not necessarily return to them later, at least to the pre-pandemic extent. In addition, many people died during that time, and so many became widowed, losing the closest person.

We recommend: What Do We Regret Most Before We Die? Final Thoughts and Words

This painful experience can also be such a powerful blow that an elderly person withdraws, and falls into isolation. Contrary to what we can assume, this does not incline them to the “new opening” – more frequent contact with the environment and activation, but quite the opposite – people under the influence of mourning and loss may withdraw further.

In the research we carried out at the Senior Policy Institute on family caretakers of older people during the pandemic, respondents reported a loosening of kinship, informal, neighborhood and colleague networks, and reduced contact with institutions. All of this combined increased the feeling of being alone – in the face of the problems that were developing at the time.

As a counterbalance, however, one can note that during this period more people began to talk about seniors, their need for support, and the risk of isolation and its consequences, and this was sometimes followed by activities, even if they were grassroots, local, or pointwise.

A new instrument addressed to lonely seniors also appeared – the so-called Solidarnościowy Korpus Wsparcia (the Solidarity Support Corps), which in a modified form exists until today. Therefore, although the overall translation of the pandemic was negative and dramatic, positive side effects, such as the development of certain new forms of support also appeared. There is at least one more area of negative impact of the pandemic on the risk of loneliness among elderly people, and this is relevant even in the longer-term perspective.

What does it consist of?

Geriatricians often say about the so-called health debt – even if someone went through the pandemic relatively unscathed, then the accompanying resignation from social life, lesser motion activity and contact with fresh air, as well as functioning under conditions of stress and fear, have had a ripple effect on their health state. Many older people have become weaker, and their fitness, immunity and a sense of vitality have deteriorated. Some seniors have prematurely declined or lost in this way their ability to function actively outside the home, among other people.

How can society help seniors from the bottom up, trying to “pull them out” of this loneliness? How could we activate them and how to reach such people at all, notice them?

This is quite a challenging issue because seniors represent a very diverse group. Everyone has their individual preferences. For some, collective forms of integration – festivals, picnics – are a nice option, but some seniors do not necessarily feel good about it and are reluctant. Some of them feel more comfortable in a small group. There are also people of mature age convinced that it is “not proper” for them, that during social events there will certainly be mainly young people after all. This is associated with such cultural perceptions of the elderly, their physicality, and “shoulds,” place in the community.

We must build a more friendly and inclusive narrative and atmosphere in public life – we are all different and not everyone has to be beautiful, fit and young. In society, there should be a place for everyone because every person has their value. Of course, there are also specific activities besides that, in which one can engage – for example, volunteering. Some organizations specialize in such activities – such as the Little Brothers of the Poor Foundation, which has been running such initiatives for years. It is very important because older people often build a deeper bond with a volunteer, make friends with them, and gain a will to live through it.

The most important, however, is the kind of ordinary attentiveness and sensitivity that allows one to notice other people – including those who are not always immediately visible. Sometimes it is our neighbor, sometimes it is a stranger who asks for help. It happens that elderly people have certain needs, but they are not always able to articulate them or they articulate them in a little concealed way – for example, they ask for a favor, but what they need is contact, a conversation or a bond. I had such an experience during my volunteering.

What did it look like?

Some man asked me to teach him how to use a computer, but it turned out that the contact was much more important – sharing a meal together and the sense of being needed that came from hosting me. By the way, the computer proved to be very useful in combating loneliness once the elderly man learned to use social media.

This allowed him to get in touch with his surroundings, and even revive relationships with acquaintances and people he has not seen for decades. The role of new technologies and the importance of adapting them to the needs of seniors is therefore also a good idea that we should be mindful of. These technologies and social media, although they are partly a source of relational problems in contemporary society sometimes, can also be used as solutions, particularly in the case of non-mobile people who find it difficult to engage with their communities, but who can be taught to do it through communicators.

Moreover, centers and initiatives designed specifically for older people – such as Universities of the Third Age, senior clubs, and day rooms – are set up. These are important alternatives, especially for people who, for various reasons, do not have close family ties. However, a considerable part of the existing infrastructure of this type is oriented toward people who are still relatively agile, but what about the rest?

Are cases of abandoned seniors frequent? Those whose families leave them permanently in nursing homes or hospitals to get rid of the “problem”?

It is a very delicate topic because we often lack insight into the motivations of such families or caregivers or the circumstances in which they make such dramatic decisions. Indeed, a certain group of elderly people end up in care or medical facilities, sometimes within the healthcare system, sometimes within social services, and sometimes in the private sector. However, the proportion of this phenomenon in Poland remains one of the lowest among all developed countries.

It is not always against the will of seniors, although in fact, statistically many people treat it as a last resort rather than a dream place of stay in the final years of life. Leaving or not picking up people from hospital facilities on time when they no longer require hospitalization is a slightly separate issue. Certainly, this may sometimes be accompanied by relational abnormalities that have been built up throughout a person’s life, but in general, I feel that in a large proportion of cases, the need to go to a hospital and stay there for a long time is justified by health reasons and, at the same time, by a shortage of adequate environmental support for people with disabilities and situations where the caretaker alone can no longer manage alone.

In the care system – whether for seniors, severely and chronically ill, or people with profound disabilities – it is very important to ensure help also for the caregivers themselves, who at a certain stage may physically and mentally no longer be able to continue this care. Caring for a dependent person can be exhausting and even dangerous when it is constantly provided by one person. The caretakers themselves, and these are not infrequently people who are already not young, for example, a spouse or an adult child of mature age, are also exposed to various life, health, and mental crises, sometimes of an acute or recurrent nature. Then such a caretaker – for example, a child or a grandchild of a senior – may decide that placement of their charge in a facility is the necessary, safest option for both of them.

Most often, these decisions are rarely black-and-white and should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. I know many cases in which relatives – before they decided to refer the elderly person to an institution – had previously tried to provide care on their own for an extended period. This decision was accompanied by dilemmas and hesitations and, most importantly, when the elderly person got there, the involvement, including financial, and ongoing concern for the well-being and the further fate of the dependent person, never stopped.

We recommend: Not Just Welfare Kings and Queens: Large Families in the World of Stereotypes

Do caretakers need more help?

What in my evaluation is the major problem here is precisely the lack of support for caregivers and families of people requiring care. Additionally, the experience of caretakers should also be considered in terms of isolation or the potential threat of it. Someone might live with another person, but can they not feel lonely when that close individual, due to Alzheimer’s disease, loses many traits of their former personality and eventually no longer recognizes them? What is worth paying attention to is not only whether a dependent person ends up in a facility or not, but also what happens later with that person, to what degree their rights are respected, whether they have contact with their environment and family, how much opportunity is created for them.

This is already a broader topic for another conversation, but it certainly involves the problem of isolation to some extent. On what scale do nursing home residents also experience isolation? Just because they are surrounded by other people and staff doesn’t automatically mean their emotional needs are being met. The quality of emotional support can vary significantly between different institutions.

A lot depends on the people who work there and organize their stay, but one cannot think about it in isolation from the systemic – legal, financial, staff – reality of the functioning of the institutional care sector. It is essential to educate and prepare personnel to take care of and build healthy relationships between residents and to avoid unsatisfactory and, in extreme cases, even violent interactions, but also to facilitate and support contact between residents and their external environment as much as possible.

Translation: Marcin Brański

Polish version: Coraz większa samotność seniorów. „Możemy im pomóc”