Science

Hidden Depths: Thousands of Unknown Viruses Found in the Dragon Hole

16 February 2026

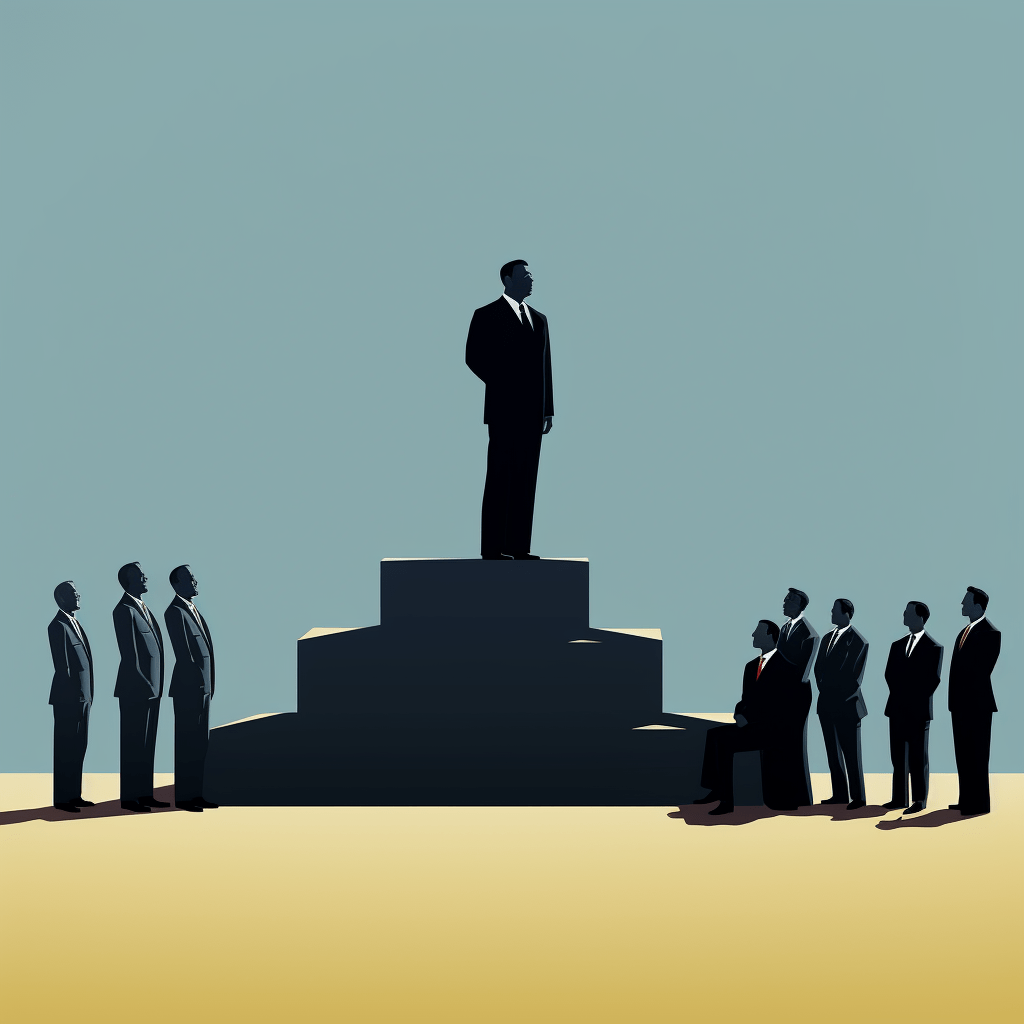

Ever since the Occupy Wall Street movements, the topic of economic inequality has risen to the forefront, extending beyond just the realm of progressive politics. Today, the increasing rates of poverty and the excessive concentration of wealth are subjects of a multitude of reports, news articles, and political discourses, as well as rigorous economic evaluations. Where will this growing focus on economic inequality lead us? Data from the Polish Central Statistical Office in 2018 revealed that a staggering 87 percent of Poles believe that “the income disparities in Poland are too large.” In 2015, this view was held by even more respondents, with over 90 percent concurring.

The topic of economic inequality is also raised in the campaigns of politicians from the major political parties, regardless of their ideological orientations. In a recent speech, leader of the Polish conservative Law and Justice party Jarosław Kaczyński claimed that: “the social inequality observed until 2015 was deliberately maintained, diminishing our nation’s standing.” On the other side of the Atlantic, during his administration, Barack Obama identified economic inequality as “the defining challenge of our era,” dedicating a substantial portion of the budget towards addressing this disparity. Bernie Sanders went as far as to describe the fight against such inequalities as “the pressing moral dilemma of our times.”

On a global scale, how does this inequality manifest itself? The “World Inequality Report 2022” presents a stark picture: the economically disadvantaged half of the global populace accounts for a mere 2,900 euros per adult when adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP). In contrast, the wealthiest 10 percent possess just short of 551 thousand euros in PPP, marking a staggering 190-fold difference. In simpler terms, the top 10 percent of global society lays claim to 76 percent of total wealth, while the bottom half manages a mere two percent. Income distribution paints a similar picture: the most affluent 10 percent accumulates 52 percent of all incomes, with the less prosperous half receiving 8.5 percent. Among the top 100 corporations listed on the British stock exchange, the salary ratio between CEOs and their lowest-paid employees stands at an alarming one hundred to one.

While Western philosophical tradition may, on the surface, appear detached from societal concerns, it possesses a distinct critique of inequality. For instance, Plato asserted that affluence can breed complacency, whereas poverty restricts the potential of the socio-economically disadvantaged. In “Leviathan,” Thomas Hobbes highlighted the potential risks of extreme wealth disparities: the wealthy might leverage their assets to challenge sovereign power, while the impoverished could grow increasingly mistrustful and rebellious.

Among the philosophers discussing inequality, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, an eighteenth-century thinker from Geneva, stands out. His personal experiences with poverty and his intellectual pursuits during the rise of capitalism offer a unique point of view. In his “Discourse on Political Economy,” Rousseau argued that it is imperative for governments to prevent vast wealth disparities. He warned of the rich’s tendency to manipulate politics and law with their money, advocating for a society where equitable regulations reflect the collective will, rather than the desires of an elite few.

Rousseau believed that the most profound impacts of inequality reside within the human spirit. To him, excessive wealth could erode moral integrity. While he acknowledged the human drive for social recognition and distinction, he posited it was beneficial only if earned through virtuous and civic actions. Unfortunately, he observed, society has shifted towards not only rewarding the accomplished with wealth but also valuing wealth itself as a mark of distinction.

Mariana Mazzucato, an Italian-American economist, echoes Rousseau’s sentiments in her book, “The Value of Everything.” She scrutinizes narratives that legitimize inequality, questioning why industrious individuals, who contribute significantly to wealth creation, should not earn more than those reaping the benefits of their efforts. Mazzucato, like Rousseau, perceives such narratives as excuses for excessive wealth accumulation. She posits that the monetary cost of a commodity does not inherently determine its societal value – hence, being wealthy does not guarantee one’s contributions are of inherent societal worth.

Throughout the 19th century, the growing poverty of the working class became increasingly evident to economists and journalists. The societal landscape was unfolding in an imbalanced manner, with a privileged elite benefitting at the expense of the less fortunate. This growing awareness of social disparities led to the establishment of new social laws, ensuring fundamental rights to healthcare, education, and employment for the underprivileged. Concurrently, discussions on inequality lead to redefining the concept of social justice, prompting a reevaluation of policies aimed at providing equal opportunities for all citizens.

By the end of the 19th century, a significant fraction of earnings was socialized to fund large-scale social welfare programs. High tax rates were imposed on the wealthiest, with the proceeds allocated for expanding public services — a move towards introducing “communal ownership.” In France, these pro-social measures also emerged as a deterrent to potential civil unrest, especially in the Third Republic when full citizenship was predominantly limited to property ownership.

However, this revised order was not merely focused on redistribution. It sought to establish democratic institutions to combat societal scourges like poverty, indifference, illness, and hunger, while also championing peacetime solidarity. The welfare state was conceptualized not just as a mechanism for promoting equality but also as a promise of a profoundly reformed society, one devoid of warfare’s tragedies and inhumane exploitation.

A study recently published in “Nature Energy” suggests that even a slight curbing of luxury consumption by Europe’s top 20 percent of energy users could lead to a greenhouse gas reduction seven times greater than cutback efforts targeting the bottom 20 percent. The research further posits that the affluent have broader opportunities to minimize their environmental impact, extending beyond mere consumption patterns to their roles as active citizens, influential investors, societal role models and responsible employees.

Supporting this perspective, data from the Stockholm Environment Institute and Oxfam in 2015 revealed that the carbon dioxide emissions of the top one percent outpaced those of the bottom half twofold. There is little doubt that global elites, including the middle class in wealthy countries, bear a disproportionate responsibility for environmental degradation. Thus, policies aimed at curtailing consumption among society’s elites can be effectively implemented through strategies that reduce social inequalities.

Opponents of inequality combat often raise the question of the limits of redistribution, asking when specifically will taking from the rich and giving to the poor accomplish its intended objective. Some liberal politicians raise alarms about potential outcomes reminiscent of Venezuela or even a Soviet-style regime. Yet, much to the dismay of libertarians, numerous leading economists, including Nobel Prize laureates, firmly argue that progressive fiscal strategies and comprehensive welfare systems have actually anchored capitalism by effectively addressing widening social disparities.

A notable voice in this discourse is Thomas Piketty, author of the widely-read “Capital in the Twenty-First Century,” which boasts over three million copies sold. In his follow-up work, “Economics of Inequality,” Piketty advocates for the re-establishment of a progressive global tax regime. Such a system, he suggests, could facilitate a seamless shift towards what he terms “participatory socialism.” Within this framework, providing universal access to education and healthcare would significantly mitigate the surge in inequalities.

Using Sweden as a case study, Piketty highlights its situation prior to World War II, when it exhibited some of the most pronounced social inequalities among Western countries. It was the sustained endeavors of labor movements over decades that yielded tangible societal benefits. It is imperative to understand that Sweden’s decline in social disparities was not merely a product of its unique culture or inherent character but a conscious political choice to replace a reigning ideology.

In addressing inequality, it is insufficient to simply spotlight stark poverty data or criticize the opulence of the wealthy elite. Instead, our collective aim should focus on championing pragmatic strategies that counteract inequality and building widespread societal endorsement for egalitarian principles. Piketty’s insights, bolstered by the chronicles of historic progressive movements, underscore a critical notion: inequalities evolve into societal challenges when we collectively recognize and address them as such — and not otherwise.

Read more on Holistic News