Science

Ghost in the Stone: AI Uncovers Prehistoric Clues That Could Rewrite Bird Evolution

17 February 2026

Utopia—a place no one on Earth has ever seen and never will. Yet, repeatedly, someone promises to lead us there, luring us with visions of a perfect society. But the path to this imagined paradise is all too real—paved with the blood and suffering of enemies, and sometimes even our own people. Does this deter everyone? Hardly. For many, the journey itself becomes the goal.

Thomas More, in the 16th century, described a land with a perfect social order and gave it the name “Utopia.” In Greek, the word can mean “good place,” “perfect world,” or “a place that does not exist.” In this imagined society, there is no money, people trust their government, and morality guides daily life.

Over time, new utopian visions sought the same kind of perfection. While ideas of the “ideal” differed, they all relied on the assumption of goodwill and honesty among both citizens and rulers. Such visions have always mattered to people. But they tend to surface most often in times of crisis – when their role becomes especially significant.

One path to an “ideal” system was laid out by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. On February 21, 1848, the German philosophers published The Communist Manifesto in London. Their vision of a perfect world arrived at just the right moment. The Industrial Revolution, which began in the 18th century, widened the gap between labor and wealth. Masses of low-skilled workers toiled in poverty with little hope for change. Frustrated and desperate, they sought a transformative idea – one that promised redemption, even if it rested on flawed assumptions, as long as it spoke to their struggles.

Marx advocated for extreme, radical change, much of it rooted in utopian ideals. He despised capitalists and saw private property as a fundamental evil. In his view, the means of production should be collectively owned to ensure employment for all. And society should be built on absolute equality.

Without getting into all the details, this vision of the world was deeply appealing to many. Marx made it clear that he didn’t need divine intervention to achieve his goals. In fact, he called religion the “opium of the people” declared that “man is the highest being for man”. And positioned the working class, or proletariat, as the collective saviors of society.

These were, in fact, additional appealing aspects of “Marxism,” offering everyone the chance to feel like a “god.” Marx didn’t concern himself with how flawed humans might interpret the “power” he gave them. Wouldn’t the idea of man as the “highest being” be seen as a claim to “supreme authority,” where justice and morality are defined by “one’s truth”? And ultimately, wouldn’t truth become an unstable and subjective concept?

Marx preferred to embrace a utopian view of human nature as truth because he believed the real problem lay elsewhere. To create a world of “equality and justice” – one without social classes or national borders – it was first necessary to destroy the existing order. And he meant that literally.

He rejected any compromise and waged an authoritarian war against those who sought a peaceful approach. Marx was uninterested in evolutionary change and indifferent to the reforms of the time. Above all, he was unconcerned with the workers themselves. As he put it, “There is only one way in which the mortal agony of the old society and the bloody birth of the new can be shortened: revolutionary terror.”

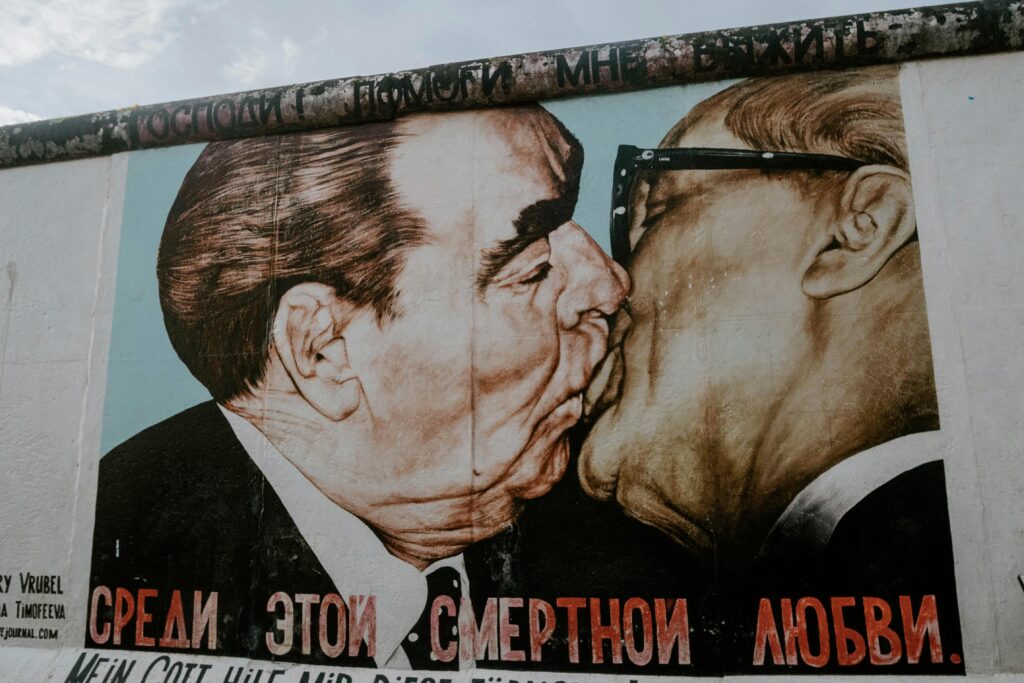

The use of terror was never just a theoretical aspect of Marx and Engels’ philosophy. Their ideas quickly found practical and eager followers. Vladimir Lenin, followed by Joseph Stalin, spread the terror of the proletariat across much of Europe. With their vision of equality and justice, they successfully drew in populations in Africa and Latin America. It’s no coincidence that The Communist Manifesto begins with the phrase, “A specter is looming over Europe,” and ends with the rallying cry, “Workers of the world, unite!”

The leader of the People’s Republic of China, Mao Zedong, also drew on the Marxist vision of the world. There, too, a utopian – and further distorted – doctrine arrived at just the right time. After his victory in the civil war, the leader of the Communist Party of China needed an ideology that would inspire the masses, especially young people, luring them with promises of power, albeit at the cost of enormous sacrifices and an ongoing battle with enemies. This struggle, unlike the Marxist theory, was meant to continue even after the victory of progressive ideas.

As Mao proclaimed, the so-called progressive war was not only acceptable but even desirable as a “just war.” “Revolutionary war is a kind of antidote. Not only will it break the enemy’s fierce attack, but it will also cleanse our ranks of all filth,” – Mao Zedong argued.

In the mid-1970s, a communist leader known as Pol Pot began to put his obsession with the ideas of Marx, Stalin, and Mao into practice in Cambodia. Like his predecessors, he envisioned a utopian society—one that was perfectly egalitarian, free from the past, religion, trade, currency, foreign influence, and personal ambition.

Believing that the path to this ideal society and perfect world required the bloodshed of his own people and the eradication of any remnants of the old order, Pol Pot declared the start of his rule as “year zero” of a new era. He fully embraced Mao’s concept of perpetual war, taking it to extreme lengths with catastrophic results.

He targeted all “enemies of the revolution,” a label that could apply to anyone, regardless of age or gender. Even wearing glasses or having smooth hands could be evidence of betrayal. Because it was a symbols of a lack of manual labor experience and a tendency toward intellectualism, which were seen as anti-people. The cost of the utopia that Pol Pot envisioned was horrifyingly high. He and his Khmer Rouge faction were responsible for the deaths of up to one-quarter of Cambodia’s population.

Utopias are not isolated ideas – they are built on intellectual foundations that entice with visions of a perfect world, promising that just “a little more” sacrifice and “certain” compromises will bring it to life. How is it that brilliant minds have been, and continue to be, drawn to ideas that have failed for generations, yet still manage to rally devoted followers?

Nobel laureates like George Bernard Shaw, Ernest Hemingway, and Jean-Paul Sartre were loyal supporters of the communist cause, even if their affection wasn’t always returned by the Soviets. Bertolt Brecht never abandoned his admiration for the dogmas of the Soviet Union, even after the official revelation of its “errors and distortions.” The German playwright simply couldn’t imagine any other path than the one that had inspired him up until then.

Sartre, though he distanced himself from the communists under various circumstances, always found his way back to them, despite being called a “jackal with a typewriter.” Meanwhile, Saloth Sâr, who would later become the infamous Pol Pot, was deeply influenced by Sartre’s lectures during his time studying in Paris.

Meanwhile, even in the final year of his life, George Bernard Shaw openly declared that he still considered himself a communist, predicting that “the future belongs to the country that carries communism the farthest and the fastest.” Finally, according to the CIA, Ernest Hemingway was allegedly a Soviet agent operating under the pseudonym “Argo.”

The list of intellectuals drawn to communism was extensive. Many remained blind to its atrocities or justified them as necessary sacrifices on the road to a greater good. For them, aggressive violence – seen as the final argument of Marxist ideology – took on special importance. They eagerly embraced it, feeling empowered and assertive in doing so. Their writings and lectures ceased to be mere academic exercises; they took on real, transformative power.

The idea of reaching a “paradise on earth” through force also fueled ordinary vanity and pride. It led to the belief that the wisdom they preached was an undeniable truth. In his book Shattered Mirror…, Prof. Wojciech Roszkowski described this mindset as “a trap for anyone who, having learned much, believes they can offer a simple diagnosis of the world and prescribe an equally simple and effective solution.”

This trap is especially dangerous because the conviction of one’s own knowledge often dulls moral sensitivity. Educated individuals may feel compelled to criticize and instruct others, yet reject moral norms. Enamored with the sound of their voices, they become deaf to even the simplest counterarguments.

Vanity is contagious. An unwavering belief in one’s greatness and the messianic significance of one’s ideas quickly attracted followers, who became, to varying degrees, mere instruments of that vision. Over time, the idea of a perfect society – meant to be the goal and justification for the sacrifices made—grew increasingly vague. Meanwhile, the actual focus shifted to dismantling the hated old order, which became an end in itself.

In the 1960s, during the cultural revolution in the West, an idea emerged that offered power, rejected moral boundaries, and, on top of that, embraced impunity and the sanctification of violence for noble causes. This quickly attracted more and more rebellious students. Everyone wanted to feel like a rebel and challenge the “old guard” standing in the way of progress. Intellectual inspiration came from figures like Bob Dylan, who would later win both an Oscar and a Nobel Prize. In the anthem of his generation, Times They Are a-Changin’, he sang to “mothers and fathers”: Your old road is rapidly aging. Get out of the new one if you can’t lend a hand, for the times they are a-changin’.

What did this look like in practice? Mark Rudd, one of the agitators and troublemakers at Columbia University in New York, later recalled fondly shouting at professors: “Against the wall, you bastard!” He pointed out how this shocked conservative teachers, forcing them to confront the “brutality, hatred, and obscenity” of their students.

For those more sensitive to the harsh realities, there was always the appealing version of the communist utopia, beautifully encapsulated in John Lennon’s song Imagine. Through this song, followers of Marx’s ideas could convince themselves they were becoming better simply by wishing for “a brotherhood of man” with “no religion or borders.” Without guilt, they could preach their “truth” about communism, turning a blind eye to the destruction it left in its wake.

Translated, edited, and compiled from the Polish version by Joanna Sarata

Read the text in Polish: Marzenie o raju na ziemi nie umiera. Piekło dostajemy w pakiecie

Science

17 February 2026

Science

17 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny