Science

Lost on the Moon for 60 Years: AI Joins the Search

23 February 2026

Our civilization deeply values history, understanding it not only as the history of a state, nation, or tribe but also as the history of one’s lineage or family. Even hunter-gatherer tribes did not abandon the bodies of their ancestors or deceased companions; instead, they meticulously buried them. Cemeteries, tombs, kurgans, and pyramids are not just testimonies of respect for ancestors, paying tribute, and ensuring their remembrance; crucially, they are an irreplaceable source of knowledge about ancient cultures for us, contemporary people. This inherent question—what we leave behind—remains central to our identity.

In antiquity, people often traced the lineage of pharaohs, kings, and emperors back to the gods themselves or at least to great heroes of semi-divine origin. This narrative of respectable ancestors was meant to build public respect for their heirs. However, the memory of family roots (whether real or invented) did not concern rulers alone.

In the Polish noble class, there was immense interest among the szlachta (nobility) not only in their own lineage but also in the ancestry of other members of their social class. Undeniably, this interest stemmed not only from searching for relatives and kin but also from the need to legitimize a given nobleman as a true one, not an imposter.

If a person could effortlessly recount their parents, grandparents, and extended relatives, their alliances and possessions, it proved they were not impersonating a noble (which was a real problem recognized and actively guarded against in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) but were genuinely one.

On the other hand, ancient chroniclers already mocked noblemen who tried to trace their origins not only to Roman senators but even—believe it or not—to the family of Jesus Christ.

In the theoretically egalitarian and plebeian Polish People’s Republic, a fashion for tracing aristocratic or at least noble roots began at a certain point. Genealogy became popular, and people even hired specialists to professionally draw up family trees, as these individuals knew how to use archives and documents (or their own vivid imagination).

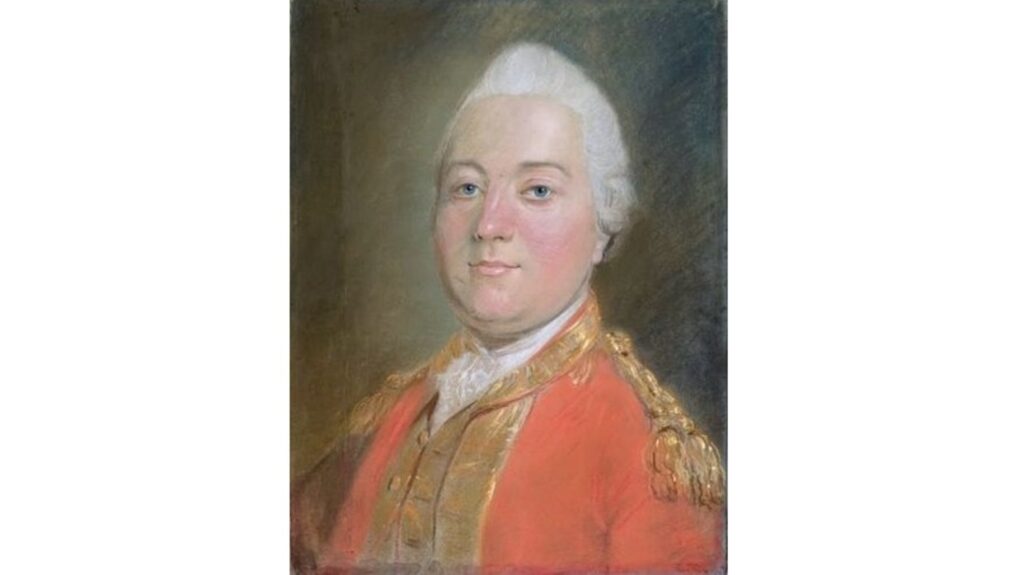

The television show Czterdziestolatek (The Forty-Year-Old) satirizes this in an episode where the main character buys an “ancestor’s portrait” in an art gallery, seeking to find his roots among the old elites as an aspiring representative of the new elite.

Hypnotic séances, meant to take people back to their past lives, also became fashionable. It always amused me that the masters of these séances usually found royal, princely, or at least knightly or artistic roots for their clients.

Of course, each of us would rather be a descendant of Alexander the Great than a starving Egyptian fellah eaten by a crocodile at the age of fifteen. But if those séances were true, it would mean that the ancient world consisted mainly of patricians, not plebeians.

And now for my family memory. On my mother’s side, I come from the Zaremba family, known in the annals of history since the Middle Ages. My ancestors included senators, bishops, governors, and generals. My great-great-grandfather, Józef Zaremba, was an influential aristocrat, Marshal of the Bar Confederation, and a general in the royal army.

Now, let me be clear: neither similar nor superior ancestry adds any splendor to me or to anyone else claiming such lineage. We ourselves must earn our place in the world and deserve respect through our own deeds and accomplishments. Ancestors—magnates, great politicians, or military commanders—can be a pleasant topic for recollection, but they cannot build our life path for us.

However, we must also acknowledge that the memory of great ancestors and respect for their achievements can, in a way, shape our reality and our future. People who have known their roots and origins for generations can more strongly identify with the state and nation they belong to. They feel a moral obligation to their ancestors, who spilled blood for that state and that nation.

Incidentally, my great-great-grandfather Józef was recounted to me from childhood, not so much through the prism of his patriotic actions or wartime victories, but because of the horrific death he suffered. Józef Zaremba was a true man of the Enlightenment—curious about the world and eager for technical novelties. He imported a special steam bathtub from Vienna and, due to a defect, died in that very tub from fatal burns.

Imagine this: a professional officer, a general, a participant and commander in many battles (both victorious and defeated)—dies not on the battlefield but on his own estate, testing a technical novelty. I always felt immense pity for his death and it always prompted me to agree with the saying, “You do not know the day nor the hour.” You survive a hail of bullets or cannon fire, only to die because a hatch jammed in a hermetic sauna-bathtub.

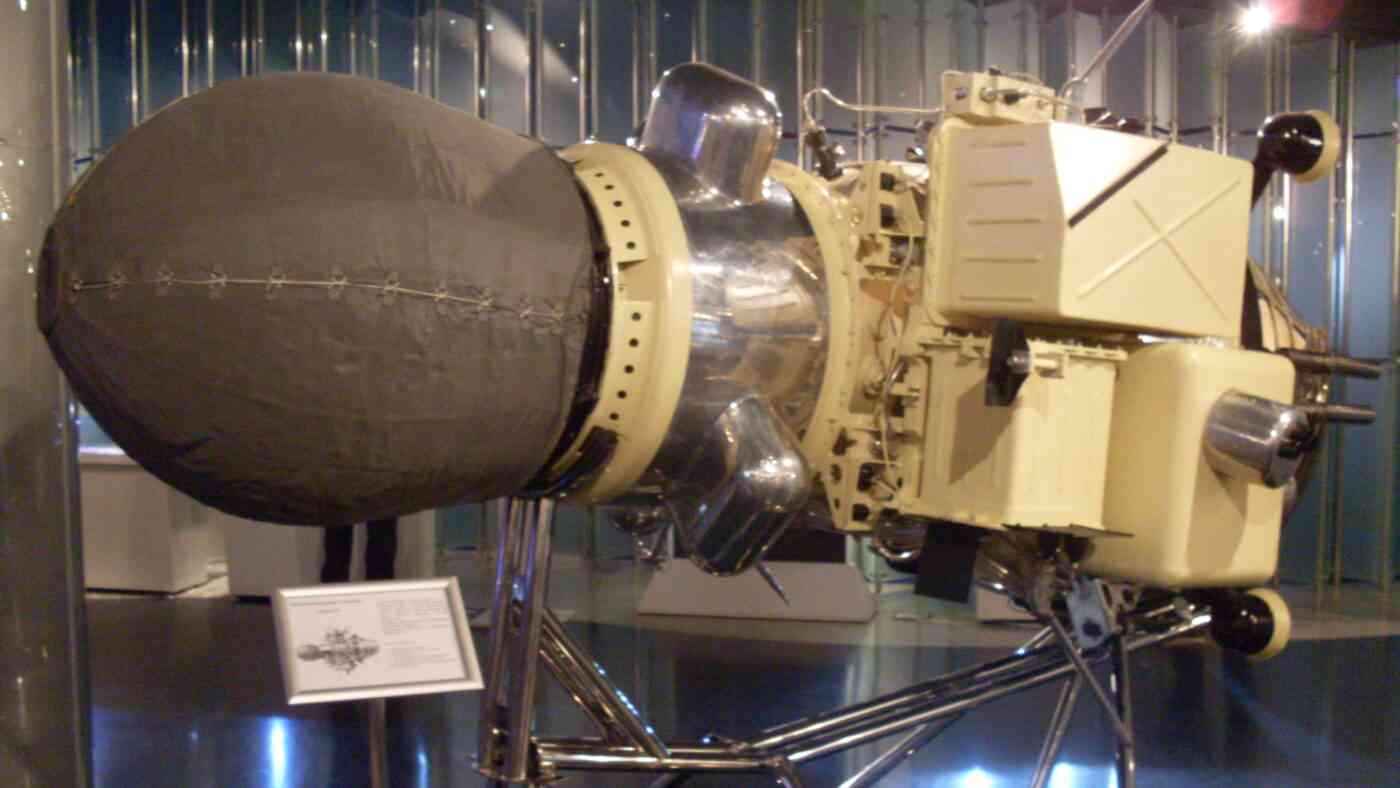

In contrast, my grandfather (no longer great-great…) Arkadiusz Piekara (on my father’s side) was not only an eminent scientist and author of academic textbooks but also worked for the Home Army (AK) intelligence during World War II, deciphering data concerning V2 rockets.

Interestingly, he began his service for the Polish Underground immediately after being released from the Dachau concentration camp. So imagine: a scientist in his thirties (not a soldier!) is released from a concentration camp and immediately engages in conspiracy activities, which threatened him with a return to a similar camp, at best.

Furthermore, speaking of the terrible occupation times: my mother’s cousin was arrested and sentenced by the communists for her participation in the National Armed Forces (NSZ); my father’s cousin was sentenced to death by the communists, later commuted to life imprisonment. My great-uncle, an AK counterintelligence officer, was murdered by communist People’s Guard bandits. Another great-uncle was executed in Katyń. Finally, my grandmother was a teacher in underground classes in the General Government.

As I have written, the merits of our ancestors are in no way our own merits. Although we can be proud of them and tell their stories, we cannot bask in their glory. I have always believed that there is no one more worthless than an arrogant, parasitic aristocrat who benefits from the name, wealth, and achievements of truly outstanding ancestors, while possessing no significant value himself. Unfortunately, such figures are all too common among the descendants of aristocratic families.

But we must keep family memories alive, pass them on to our children, and create a generational relay so that future generations know who they are, where they come from, and what their family roots are.

Because if we strip children of the memory of their ancestors, the memory of the land where those ancestors grew up, and the memory of the ideals that guided them, it will be all the easier for them to become “internationalists,” “cosmopolitans,” or “Europeans.” People without roots and without substance. And because of this lack of roots, they will be vulnerable to being swept away by every dangerous or dirty wind. Ultimately, our focus should be on what we leave behind.

Read the original article in Polish: Jacek Piekara o pamięci pokoleń: Bez korzeni porwie nas każdy wiatr

Science

22 February 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny