Science

Have We Been Lied to for Years? The New Food Pyramid Divides Doctors

09 March 2026

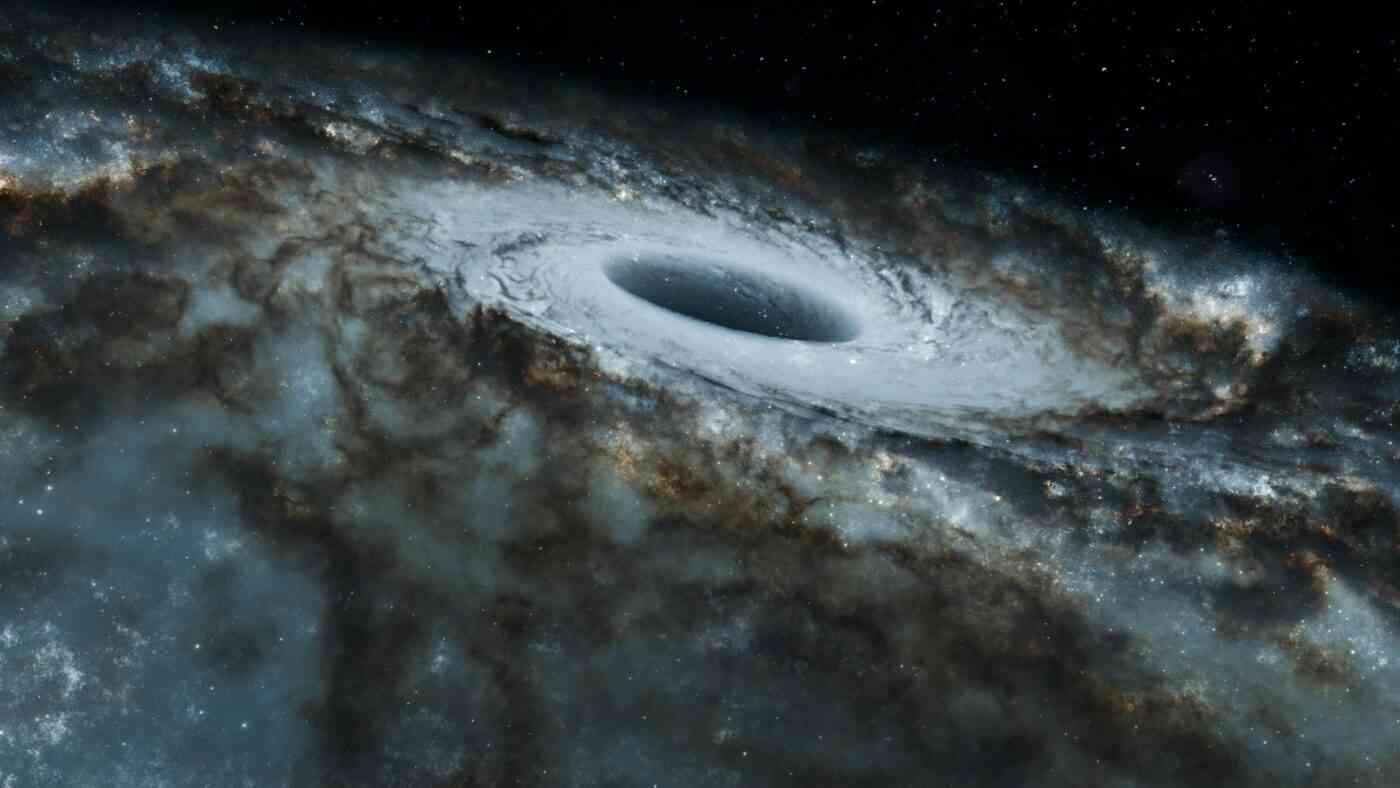

The James Webb Space Telescope has, for the first time, allowed scientists to peer into the very mechanism of a galaxy's demise. This 11-billion-year-old object appeared deceptively calm—showing no signs of cosmic collisions. Yet, it mysteriously stopped birthing stars. The culprit? Webb’s black hole observations reveal a slow, calculated starvation rather than a violent explosion.

The galaxy GS-10578, nicknamed “Pablo’s Galaxy” after the astronomer who first observed it, sits at the heart of this mystery. Massive and ancient, it weighs about 200 billion times more than our Sun. While it formed most of its stars shortly after the Big Bang, it suddenly “went quiet.” Researchers have now confirmed that the galaxy died not from violence, but from a lack of cold gas—the essential fuel for stellar birth.

Data from both the Webb telescope and the ALMA array in Chile point to the supermassive gravity well at the galaxy’s center. Instead of tearing the galaxy apart in a single blast, Webb’s black hole acted as a cosmic chokehold. It repeatedly heated the surrounding gas, effectively cutting off the supply of cold matter needed to ignite new stars.

This black hole pushes gas out of “Pablo’s Galaxy” at a staggering rate—equivalent to tens of solar masses every year. At this speed, the black hole could deplete the galaxy’s entire fuel reserve in just 16 to 220 million years. In cosmic terms, that is a mere blink of an eye compared to the typical lifespan of a star-forming galaxy.

The significance of this discovery lies in the direct observation of “slow starvation.” The galaxy looks like a peaceful, rotating disk with no scars from past collisions. This rules out external galactic wars as the cause of death. Instead, the black hole’s recurring bursts of activity acted as a heater, pushing gas away and preventing it from ever returning to the disk.

You don’t need a single cataclysm to stop star formation; you just need to stop the flow of fresh fuel,

– explains Dr. Jan Scholtz from the University of Cambridge.

This finding also explains why some massive galaxies in the early universe appear “older” than they should—their growth was cut short by their own central engines.

The mission is also shedding light on “Little Red Dots”—mysterious objects that share traits with both dense galaxies and active supermassive black holes. For years, they didn’t fit neatly into any scientific category.

New research suggests these dots are actually infant supermassive black holes shrouded in thick cocoons of gas. By analyzing the light signatures of 30 such objects, scientists found that their emissions perfectly match models of a black hole trapped in a dense gas cloud. This “cocoon” absorbs X-ray and radio radiation before it can escape into space.

When researchers recalculated the mass of these objects, they found they were 100 times lighter than previously thought.

These are, to our knowledge, the lowest-mass black holes at high redshift,

– the team wrote in their study published in Nature. As our understanding evolves, each glimpse of Webb’s black hole data brings us closer to mapping the forces that shape our universe.

Read this article in Polish: Teleskop Webba odkrył, co zabiło galaktykę. To nie był wybuch