Science

Hidden Depths: Thousands of Unknown Viruses Found in the Dragon Hole

16 February 2026

Every child in the US learns the words of the Declaration of Independence. There’s an unusual formulation in it: that every human has the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Those words have shaped the American mentality, says Dr. hab. Zbigniew Lewicki, a specialist on the US and political scientist.

Wojciech Harpula: Since the Soviet Union fell, the United States has been the world’s sole superpower, a constant reference point in global politics, economics, and culture. What do you think is the essence of the country and nation in the basic civilizational sense?

Prof. Zbigniew Lewicki*: In my view, there are a few features that reflect on America and Americans, the combination of which is unique and characteristic to that country and nation.

First, the history of the US is fully documented, which allows us to trace its origins and development. Since 1620, when the Mayflower passengers built Plymouth in New England, which is widely considered the beginning both of British expansion in the New World and also of the US, everything’s been set down in black and white. From further legislation and events to debates and disputes. Americans know who they are: where they came from on this continent, why and how their country was created, and how it developed. This gives them a sense of certainty and solidity, positioned on the sold ground of facts, not guesses. In their history, unlike in Europe, there’s no place for the “darkness of history,” suppositions, hypotheses, and legends.

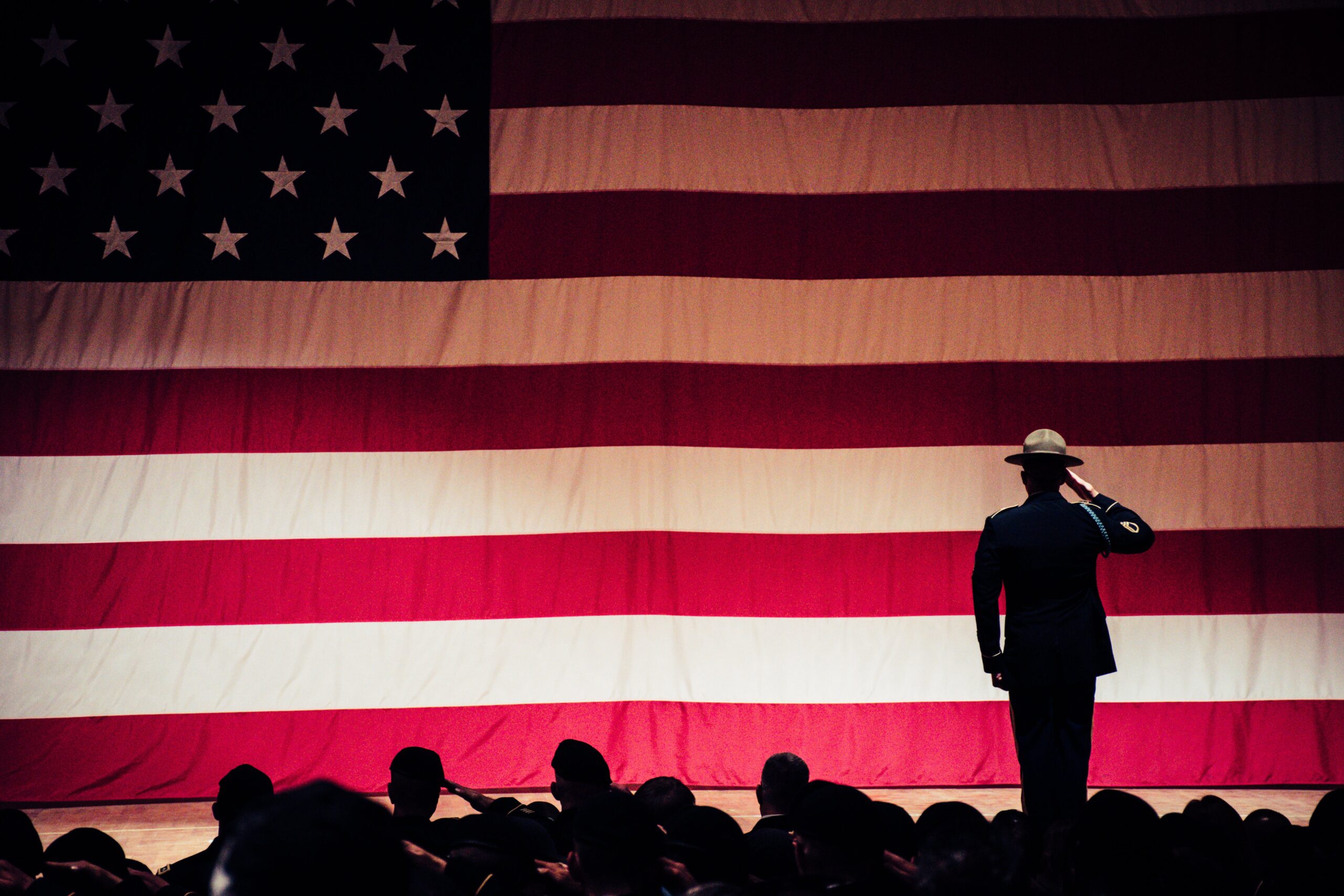

Second, America is a country that was conceived in war. The history of the British colonies in the New World abounded in military conflict and the history of the US as a state begins in an armed clash with Great Britain. The saying that Europe’s from Venus and America’s from Mars is largely true. For Americans, war, fighting, and death in battle are nothing unusual. They have great respect for those who die on the battlefield, but they don’t regard that as a special sacrifice. Americans and American politicians believe that war is can be a necessity. This makes them different from Europeans.

Probably because the history of Europe is basically a sequence of wars, with the cataclysms of the First and Second World Wars at the forefront. Americans lack this experience.

Since their Civil War, there’s been no fighting on American soil, it’s true. However, the US participated in both world wars and suffered heavy losses in the struggle against Germany and Japan. Americans commonly believe that they were fighting for a just cause and that the victory of good over evil demanded sacrifice. They were prepared to make them. This “war” feature and accepting violent means of resolving conflicts doesn’t refer exclusively to the inner sphere. In this, until recently, the standard was striving for a community of views and decisions – another characteristic of America and Americans.

Today that’s rather lost its relevance.

It has. It’s currently working out less and less well, but there’s no doubt that US citizens from the very beginning of that state’s functions have applied the principle that dispute must lead to a solution that lies somewhere between the two opposing sides. And after the conflict, even the revolutionary one, has been resolved, the adversaries shake hands and go their own way. In Europe, there’s a view that in a situation of differing opinions, someone has to win and someone has to lose.

Someone is right, someone is not. The Americans, at least until recently, knew very well that a compromise was a situation neither side left fully satisfied. However, in that no one has completely lost the dispute, a platform has been established for further joint action. Please note their specific custom that the loser of an election officially then declares that they’ve lost. This closed the procedure of counting votes, and both the loser and winner shook hands. In Europe, such a custom did not happen. American politics knew heated disputes and debates reflect conflicting interests of individual social groups.

However, these were never “life or death” clashes. As a rule, they managed to reach a compromise that was more or less acceptable to both sides. I’m talking about this in the past tense because in the past few years we’ve seen decisive changes for the worse in this area. Time will tell if it’s possible to revive a good tradition.

And since we are talking about politics, what’s also extremely characteristic of Americans is the way they define their position as citizens in relation to state structures. In US English, the the “government” actually means management. What we in Europe call government, that is, people performing managerial functions in the state, is “administration.” Americans believe that the secretaries – that is, ministers in our language – in Washington, D.C., are supposed to manage an institution called the United States. However, they have no power to govern the people.

They are hired workers. They weren’t elected to tell free citizens how to live. Americans don’t feel governed by anyone, they don’t feel subjected to some structures in the nation’s capital. On the contrary, the state and its structures work, among other things, to ensure that citizens enjoy their rights and freedoms as fully as possible.

I once took a taxi in a city in the US. The driver drove through a yellow light at an intersection and just behind us was a police car. I asked the driver if he wasn’t afraid to drive through a yellow light when the police were watching. He replied that “I’m not worried because they didn’t see what color the light turned when I was entering the intersection.” I began to explain that it was the police, they could stop him and fine him. Then the driver turned to me, saying: “You’re from Europe, right?” That’s what it’s all about. Americans in generally don’t feel governed. They don’t have European respect for the state, its bureaucracy, institutions, and functionaries.

Why?

Because every child in the US learns the words of the Declaration of Independence. There’s an unusual formulation in it: that every human has the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Those words shaped the American mentality. No one in school says to me or to you “Dear, you have the right to liberty and happiness.” In school we were told, and it’s probably also said today, that everyone has their duties and tasks to do.

We’re taught that we should conscientiously do what parents, school, society, homeland, and finally the government expect of us. Nobody talks about the right to pursue personal happiness in European schools, while Americans hear from the very beginning of education that “You have the right to liberty and happiness.” That document hangs in every school. This establishes your thinking about your role in the world, the state, and the collective.

This also results in the “American dream” and the belief that each person relies on themself, and that due to their own abilities and efforts, regardless of place of birth and social background, they can attain wealth and position.

Yes, but this isn’t the only source of that attitude. This conviction also stems from the historical path that the Americans have gone through. When settlers appeared in America in the 17th and 18th centuries, for a long time, each held the right to several dozen or so acres of land for free or at low cost. But they had to locate that land, register ownership in the surveyor’s office, and above all develop it, that is, clear it of century-old trees. It wasn’t an easy job. The nearest neighbor lived a few or a dozen miles away. Some new arrivals from a very heavily socialized Europe, where they lived in rural clusters or urban crowds, couldn’t bear the feeling of loneliness.

With no one to help those settlers, society developed a sense that the best government was one that had as little to say as possible. Government is there not to disturb, not to place restrictions or barriers on free people. They can’t expect help from the government so they don’t want it to interfere in their lives. They pay taxes – that’s enough. And for a very long time, the state in the United States functioned that way, with the developmental field left very wide for individual entrepreneurship.

The state’s role increased with reforms by Franklin Roosevelt during the Great Depression, and later under Lyndon Johnson and Barack Obama, yet to this day there are very few administrative restrictions on doing business. Specific regulations vary depend on the state you’re in, but in general one can start an economic venture practically without consent or permits. To open a restaurant or grocery store, you mostly have to take into account sanitary control.

What’s also important is that in America, you can start from scratch more than once. It’s said that one can succeed in building a business the fifth or sixth time. If someone went bankrupt honestly – didn’t cheat anyone, didn’t steal anything – they can start over, with a clean slate. Americans assume that everyone has the right to make a mistake on the path to pursuing happiness.

And one more factor that strongly distinguishes the US from Europe: one can achieve great success no matter where or in what family they were born. If I am talented, I can get a lot of money and no one wonders who my parents or grandparents were. There is no exaggeration in saying that it remains a country of great opportunities.

Isn’t that a myth? Whites’ dominance from the East Coast is evident in many spheres.

Of course, parents’ good connections always help children. That rule works at any latitude, the US is no exception. However, social mobility is much higher than in Europe. America’s intellectual elite is concentrated on the East Coast. We read their newspapers and watch TV and shape opinions about America according to what elites there say, but that doesn’t mean they shape the system and values. What’s important, elites there consciously work for the social advancement of talented individuals.

There’s a common belief that when you make a lot of money, some of it should be given to the community. Hence, thousands of foundations fund university scholarships for talented young people. In America, it costs money to get an education, but if one is capable and hard-working, they can overcome the barrier of lack of money thanks to the whole system of talent support. A classic example of this is Barack Obama’s life path.

You’ve talked about the specific characteristics of America and Americans. I would add the conviction of its uniqueness and the special role it has to play in the world.

I agree, but that isn’t a specific trait for Americans. Many nations consider themselves unique and endowed with a special mission. However, there’s no doubt: Americans believe their country is unique and the world should follow its example.

Where did this conviction come from?

The sources were religious. The 17th-century settlers, especially the Puritans, were convinced that the task entrusted to them by God was to build a new, happy state and await the second coming of Christ. They thought they were chosen by God, who assigned them the task of building a new community that would serve as an example for the whole world. This belief took the form of the concept of Manifest Destiny, that is, “Revealed Destiny”.

We recommend:

The term was first used in 1845 by Democratic Review editor John O’Sullivan. The concept was never formalized or made strictly concrete. Later, various interpretations of it would made. In general, it expressed Americans’ faith in the mission assigned to them by Divine Providence to spread forms of American democracy and freedom – initially on the North American continent then throughout the world.

Many researchers see the modified concept of Manifest Destiny – especially its most important element, belief in the “mission” of Americans, the “mission to spread democracy” in particular – continuing to influence the justification of US foreign policy and Americans’ understanding of their role in the contemporary world.

Americans are convinced of their perfection. They believe that as a collectivity they’re the most ideal creation in the world and their mission is to spread the values they consider beneficial to all people and nations. According to them, free markets and free media guarantee individual freedom and ensure the development of states. They are convinced that if everyone shares their values, they’ll become happy.

Every nation considering itself special falls into the trap of self-conceit and thinks it is permitted more. That’s why Americans aren’t perfect, that’s clear. They have armed interventions on their conscience, and political and economic expansionism is also not unfamiliar to them. They make mistakes in attempting to impose democratic solutions, in Iraq, for example. The success of the postwar democratization of Germany and Japan brought a large part of the American political elite to feel that a libertarian model can be introduced in every corner of the globe. Americans consider their political and economic model universal, but it isn’t. The example of Iraq has shown this clearly. However, I still think that America, taking the power of the state into account, doesn’t behave badly towards the world.

What do you mean?

Great powers always act on their scale. They have global interests and they watch over them, that’s completely normal. Relations between the US and other countries are asymmetrical, but it’s difficult for them to be different since today it’s the only superpower. However, it should be noted that they had reached the status of a superpower at the beginning of the 20th century and didn’t use it for territorial expansion. The Americans were never colonizers, except for the occupation of the Philippines. They didn’t force other people to speak English, play baseball, or drink Coca-Cola. They didn’t behave brutally, even though they had a sense of their power.

If I were a Latino, I would have lots of doubts.

Yes, about Latin America, one can speak of contempt Americans had for those from the South. This sense of superiority has two sources. The English colonies in the north were liberated from the rule of the metropolis at about the same time as the Spanish colonies in the south: half a century’s difference isn’t much. The colonies in the north were able to communicate. They formed a strong federation that was able to define its goals and later expanded to almost that whole continent. This wasn’t at all obvious, because the religious, economic, and political differences between the English colonies in America were very large. Whereas the colonies in South America were unable to cooperate. They divided into several countries, often antagonized and waging fierce wars.

The North Americans despised those from the South, who were unable to create an efficient state organization. They regarded them as less civilized people, unable to reach a compromise for the common good. In the 19th century, there was also an element of disregard resulting from the ineptitude of Mexico’s actions. During the war of 1846–1848, the Americans with relatively small forces defeated a much larger and much better-prepared Mexican army. Mexico then lost half of its territory to the US. The Americans concluded that Latinos do not deserve their recognition and respect.

This conviction has proven to be permanent. The United States most often intervened in the countries of South America, brutally guarding its political and economic interests. Another thing is that the interventions undertaken there during the Cold War were motivated by rivalry with the USSR.

In the 19th century, America isolated itself from the world. Why did it decide to enter the international arena, and over time began to play first fiddle there?

I don’t use the term isolationism in relation to the United States. I consider it incorrect. America had no significant belief in isolationism. If anything, it was unilateralism, that is, one-sidedness in international relations. Even the doctrine of President Monroe, presented in his 1823 annual address to Congress, though cited as evidence of isolationism, didn’t mention it at all. It stated that Europe shouldn’t interfere in the affairs of the American continent and that the US wouldn’t interfere in the affairs of European states and their colonies.

That’s it. In the 19th century, no one considered America a powerful country capable of influencing the world’s fate. However, as early as 1894, it had become the world’s first industrial power. It was a dynamically developing country with huge demographic potential and the power to attract. It became a country capable of acting on a global scale. The first president who decided that America should get involved in improving the world was Woodrow Wilson. He held office in the White House from 1913 to 1921. According to him, the US was supposed to be a force that cares about morality, order, and justice in international relations.

His beliefs resulted primarily from religious reasons. He imperfectly understood morality, from our point of view. On one hand, he believed in the need for good; on the other, he was a racist. He saw no contradiction in this. He was convinced that his vision came from God and that everyone should agree with it. When the US supported the eventual victors during the First World War then found itself in a camp of countries rearranging the world map, the basis for many decisions was a peace program called Wilson’s Fourteen Points. Then that the US spoke loudly for the first time about issues that until then had been completely outside their sphere of interest. Who in America ever thought about Serbia, Romania, Montenegro, or Poland? It was Wilson who pushed for the creation of the League of Nations, that is, an organization that would care for peace in the world. This idea was rejected by Americans. The United States returned to a policy of unilateralism, it refused to be subordinated to any collective decisions.

But their strength was obvious. Europe was devastated by war, and America remained intact. When it was necessary, the Americans were active in the international arena: they organized a Washington conference limiting the fleet size in the world, they were the initiators of the Kellogg-Briand antiwar pact, and they tried to stop Japanese expansion in Manchuria. However, they didn’t think it was their mission to fix the world. During the Second World War, it was the world that knocked on their door when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor then Adolf Hitler declared war on them four days later. We know how history unfolded: two superpowers emerged victorious from the war and basically divided the world into two antagonistic blocs. The rivalry was won by the camp of democracy and capitalism, the US became the only world power, and an “end of history” was announced.

The US became the “police force of the world” and began to “export democracy” with often a miserable result. Do Americans find it difficult to understand or accept the fact that not all states and nations consider their sociopolitical model optimal?

Americans have another special feature: they don’t care about criticism at all. They accept it because they consider it irrelevant to them. When young people threw jars of red paint at the Soviet embassy a long time ago, Moscow always sent expressions of indignation and government notes. At one time, I participated in protests in front of the US embassy in connection with the Vietnam War. Usually, the ambassador came out and said: “It’s great that you’re protesting, that’s freedom, that’s what you should do.” Americans have no problem with the fact that someone doesn’t accept their actions. They just keep doing their thing. They’re convinced that they are doing the right thing and if someone thinks otherwise, they’re wrong. In our cultural circle, it’s rather common to think that nothing better than democracy and free market has been invented so far. The fact that the world’s strongest country is guarding these values is certainly not a bad circumstance.

You may also like:

*

Dr. hab. Zbigniew Lewicki

Associate Professor of the University of Warsaw and Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University, Americanist and political scientist. From 1990 to 1995, he was Director of the Department of America at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He headed the Centre for American Studies at the University of Warsaw and worked at the Institute of the Americas and Europe at the University of Warsaw. He is the Chairman of the Council of the Polish Institute of International Affairs.

Tłumaczył: Marcin Brański