Truth & Goodness

Sickles, Hammers, and Dollars: The Capitalist Miracle of “Red” Vietnam

01 March 2026

The residents of the Balkan Peninsula are among the most superstitious people in Europe. While statistics confirm this trend, one only needs to observe daily life to see it in action. Interestingly, the majority of the population considers themselves deeply religious, yet they see no contradiction between their devotion to God and the practice of ancient Balkan mysticism.

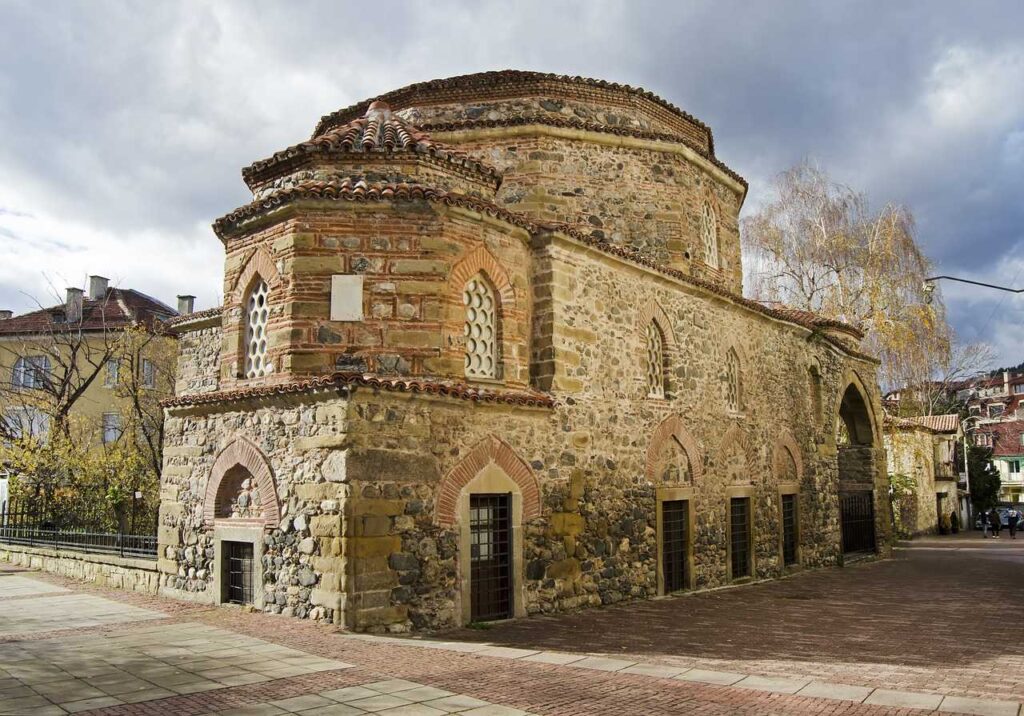

For centuries, Christianity (primarily Orthodoxy and Catholicism) has coexisted in the Balkans alongside Islam, which arrived during the Turkish expansion at the end of the 14th century. Serbs, Montenegrins, and Croats who embraced Islam earned the historical name poturczeńcy (those who became Turks).

Montenegro’s most famous epic, The Mountain Wreath by Petar Petrović Njegoš, addresses this subject. Njegoš was an extraordinary figure—a prince, the head of the Orthodox Church, the leader of the state, and the greatest poet in Montenegrin history. According to legend, he achieved more for his country in the bedrooms of European politicians than during official talks.

The Turks used force or bribery to Islamize Balkan Slavs. Today’s Bosnian Muslims descend from Serbs and Croats who converted to Islam. Although religion fueled conflicts and wars, the boundary between Islam and Christianity in the Balkans remains fluid. This makes the region’s legends and secrets a source of constant fascination for the rest of Europe.

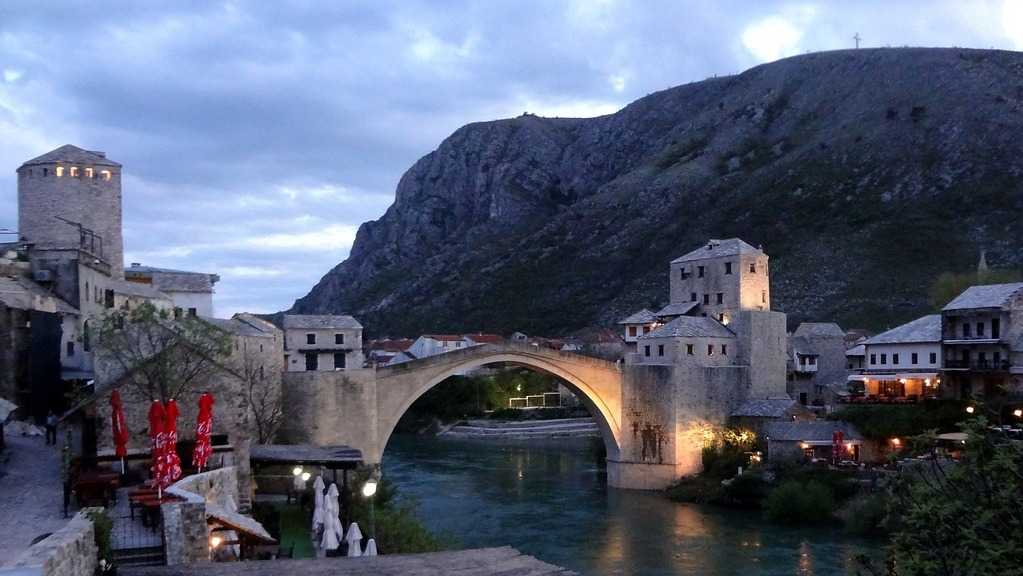

Before the war in Yugoslavia broke out, cities like Sarajevo showcased a unique landscape. Orthodox churches, Uniate churches, Catholic churches, synagogues, and mosques stood side by side. Neighbors visited each other during religious holidays and celebrated together. How did they combine such different beliefs? These stories remain part of the region’s mysterious past.

The Yugoslav Nobel Prize winner, Ivo Andrić, beautifully described this harmony. Bulgarian scholar Maria Todorova wrote:

“People and gods meet and pass each other on the bridge and at the crossroads. In the Balkans, they merge in a complex process of contact-conflict. This creates types that differ from the ideal forms found in religious and ideological doctrines. In the evolution of humanity, the Balkans act not as a transition zone, but as a space.”

This image may seem idyllic, but reality often brought bloody conflicts, such as the struggles between Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks during World War II. Later, during the era of socialist Yugoslavia, Tito fought against religions in an attempt to atheize the population. He dreamed of creating a single Yugoslav nation, which required replacing religion with atheism or “Titoism.” Many Yugoslavs, tempted by quick career advancement, abandoned their religious roots.

Religiosity returned as Yugoslavia collapsed, becoming a tool in political struggles and a way to distinguish Serbs from Croats and Bosniaks. These “conversions” often produced both funny and embarrassing stories. One famous incident involved a Serbian politician who nonchalantly smoked a cigarette during a televised church service. However, many people found sincere faith. Medjugorje became a Catholic symbol, while wealthy Islamic states supported Bosnia and Kosovo by building mosques and Quranic schools. In central Bosnia, Wahhabis—the most radical branch of Sunni Islam—began to settle. After the wars, tensions replaced the old symbiosis.

According to a survey from three years ago, over 60% of residents in Bosnia and Herzegovina believe in life after death. Over 50% of Croatians and about 40% of Serbs share this belief. For comparison: Poles declared this faith most often (over 64%), while Czechs and Estonians (barely a dozen percent) showed the least interest. Interestingly, far more respondents describe themselves as religious—averaging between 65% and 85%.

While we lack precise data on how many people believe in magic, most observers agree that Balkan residents are the most superstitious in Europe. Many beliefs mirror those in Poland. For example, an itching left palm predicts money, while the right one means meeting someone. Breaking a mirror brings bad luck. When making a toast, you must look your partner in the eye; otherwise, you face seven years of failure in the bedroom. And remember: only alcohol counts for a proper toast.

The examples are endless. However, it goes beyond simple superstitions. In the Balkans, people frequently visit fortune tellers to hear prophecies or even to order a spell. They might request a “hex” on someone they dislike or, less commonly, a positive spell to spark love or financial success.

Eastern Serbia, near the Romanian border, serves as the heartland of witches. Vlach communities, known for their passion for sorcery, inhabit much of this region. This is the place to go if you want to discover the most mystical secrets of the Balkans. Tourists also travel here to witness local rituals. You can find shamans who enter trances to prophesy. Even young, educated professionals from large cities visit these famous witches.

The rituals and ceremonies here evoke fear. This leads us to the most interesting and macabre custom: the “Black Wedding” (a tradition also found in parts of Russia and Ukraine). If a person died before marrying, the family organized the wedding and reception after their death. The bereaved fiancé or fiancée participated alongside the coffin of the deceased. The family then hosted a party with food and alcohol, followed only then by the funeral and a heavily “spirited” wake.

To this day, people in the Balkans drink rakia at the grave. After the funeral, the family sets up a table with alcohol just a few yards from the burial plot. Each guest pours a few drops on the ground—for the peace of the soul—and then drinks the rest. Only then do they move on to the wake. People also still eat at gravesites and leave symbolic food for the deceased, especially during holidays. These traditions show how thin the line is between life and death. In the same way, the boundary between faith and Balkan mysticism remains unclear.

Read the original article in Polish: Kraina trzech religii. Tu wiara miesza się z przesądami

Truth & Goodness

01 March 2026

Zmień tryb na ciemny